Scroll to:

Techno-Ethical and Legal Aspects of Cyberbullying: Structural Analysis of Power Imbalances in the Digital Sphere

https://doi.org/10.21202/jdtl.2025.19

EDN: bvlgsu

Abstract

Objective: to conceptualize cyberbullying from the viewpoint of law and technoethics; to analyze the power imbalance in the digital environment as a fundamental factor of causing harm online.

Methods: the work uses a conceptual and analytical methodology based on an interdisciplinary analysis of the theoretical provisions of law, technoethics, philosophy of technology, and social psychology. The methodological tools are complemented by constructing unique conceptual models through analyzing the structural factors of the digital space, developing causal relationships and creating a taxonomy of cyberbullying forms. Special attention is paid to the comparative analysis of regulatory approaches of different jurisdictions and the identification of gaps in existing legal norms.

Results: the research established that cyberbullying is a complex multilevel phenomenon that occurs at the intersection of the architectural features of digital platforms, the asymmetry of technological competencies between participants in interactions, and the systemic fragmentation of legislative regulation. It identified the critical gaps in key international legal instruments, manifested in the lack of unified definitions of cyberbullying, insufficiently elaborated mechanisms for cross-border cooperation, and irrelevant addressing of the digital environment specifics. The author analyzed the fundamental ethical issues related to automated content moderation based on machine learning algorithms, the distribution of responsibility between platforms, government regulators and individual users, and the contradictions between ensuring security and maintaining user autonomy. Four main types of power imbalances were identified: technological, informational, social, and institutional; each of them requires specific strategies to overcome.

Scientific novelty: for the first time, the article proposed a comprehensive approach to analyzing cyberbullying as a structurally determined abuse of digital power through the prism of technoethics. The developed conceptual models provide new tools for understanding the distributed nature of responsibility in the digital ecosystem and forming ethically sound prevention strategies. The author introduced a concept of information misuse as a central mechanism of systematic abuse of power in the digital environment.

Practical significance: the research is aimed at legal scholars, public officials, and digital platform developers. It offers practical solutions in the fields such as ethical audit of algorithms, creation of hybrid moderation systems involving artificial intelligence and humans, formation of international task forces, and development of human rights-based principles of digital literacy. The author’s proposals may help to create a safer, more accountable and inclusive digital environment for all participants.

Keywords

For citations:

Spyropoulos F. Techno-Ethical and Legal Aspects of Cyberbullying: Structural Analysis of Power Imbalances in the Digital Sphere. Journal of Digital Technologies and Law. 2025;3(3):472-496. https://doi.org/10.21202/jdtl.2025.19. EDN: bvlgsu

Introduction

Cyberbullying, although increasingly prevalent, lacks a universally accepted definition both in Europe and internationally (Smith et al., 2013). According to UNICEF, it is defined as “bullying with the use of digital technologies”1. Similarly, the European Commission2 describes it as “repeated verbal or psychological harassment carried out by an individual or group, leveraging digital platforms to disseminate harmful content, such as abusive messages or embarrassing photos, with the aim of distressing or humiliating victims”.

The United Nations recognizes cyberbullying as a form of online violence characterized by an imbalance of power, anonymity, and a broad audience. Unlike traditional bullying, a single harmful act online can constitute cyberbullying due to the permanent and far-reaching nature of digital content3. This evolving definition reflects the unique risks posed by digital platforms, including constant accessibility and the replication of harmful material, which exacerbate the victim’s vulnerability (Langos, 2012; Menesini et al., 2012; Slonje & Smith, 2008).

Scholarly definitions often build upon Olweus’s (1993) traditional bullying framework, emphasizing the use of digital tools, intent to harm, and repeated actions (Englander et al., 2017; Mouzaki, 2010; Juvonen & Gross, 2008). Central to cyberbullying is the aggressor’s exploitation of technological advantages to target victims who may lack the means to defend themselves, as well as the anonymity and publicity provided by digital platforms (Kowalski, 2018; Smith et al., 2008; Nocentini et al., 2010; Hinduja & Patchin, 2006). Li’s (2007) metaphor, “New bottle but old wine,” aptly captures the way cyberbullying mirrors traditional bullying while incorporating the distinct features of digital technology.

Artificial intelligence (AI) introduces additional complexities to this landscape, serving both as a tool for addressing cyberbullying and a potential challenge. AI-powered systems are increasingly used to detect harmful content, moderate interactions, and prevent the spread of abusive material. However, these systems often face limitations, such as difficulties in understanding context, cultural nuances, or distinguishing harmful intent from satire or criticism. Additionally, aggressors have begun exploiting AI tools, such as deepfakes or automated bots, to amplify harm, manipulate content, or target victims on a larger scale. These developments underscore the need for robust, transparent, and ethical AI systems to counteract cyberbullying effectively (Hasan et al., 2023; Raj et al., 2022).

The psychological and social consequences of cyberbullying, particularly among children and adolescents, are profound, ranging from mental health issues to damaged relationships (Campbell & Bauman, 2018). Additionally, specific harmful behaviors, such as the unauthorized dissemination of explicit images (“sexting”), further highlight the dangers posed by cyberbullying (Katerelos et al., 2011; Chakraborty et al., 2021).

Despite these insights, the absence of a standardized definition continues to hinder global efforts to combat cyberbullying effectively. Addressing this gap requires comprehensive approaches, including educational campaigns, digital literacy programs, stricter regulations, and international collaboration. Recognizing the unique dynamics of cyberbullying, including the evolving role of AI, is essential for developing interventions that create safer and more equitable digital spaces.

1. The Misuse of Information as a Systematic Abuse of Power in Cyberbullying

The misuse of information within digital environments has become a defining feature of cyberbullying, representing a systematic abuse of power. In these contexts, aggressors exploit technological tools to manipulate, control, and harm others, capitalizing on the unique affordances of the internet. Unlike traditional forms of bullying, the digital sphere enables perpetrators to transcend physical boundaries, leveraging the scalability of online platforms, anonymity, and the permanence of digital content to amplify their actions (Courakis, 2005; Lazos, 2001; Furnell, 2006).

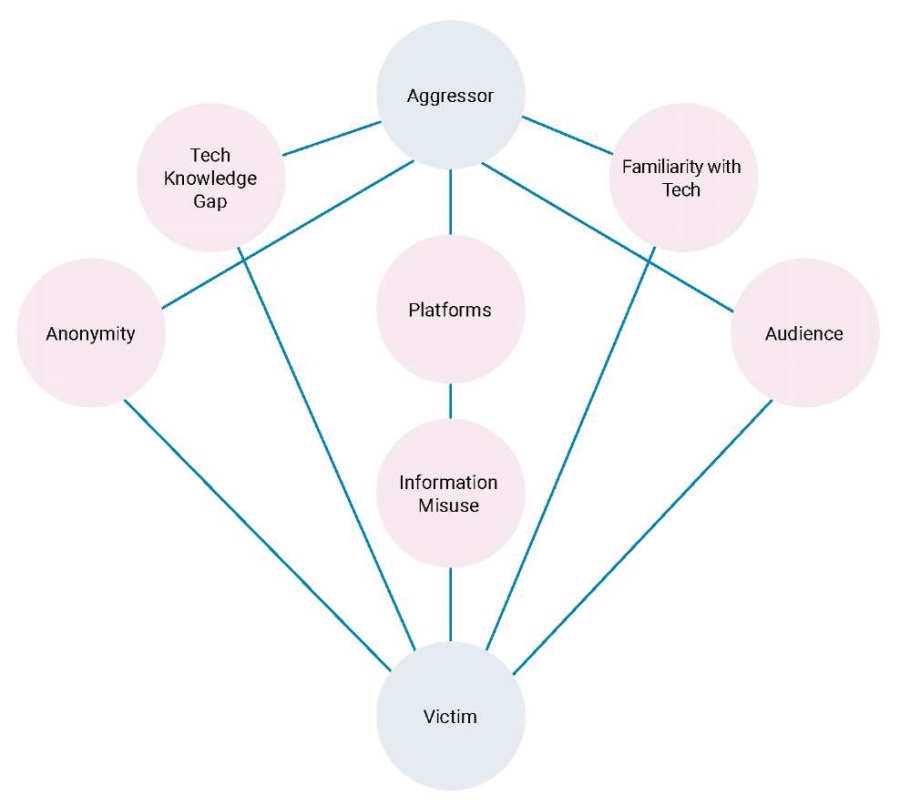

Central to this phenomenon is the Enhanced Cyberbullying Power Imbalance Model (Figure 1), which provides a framework for understanding the dynamics of power in digital bullying. The model highlights key factors that facilitate harm, including the aggressor’s ability to manipulate information, exploit anonymity, and reach wide audiences. These elements not only empower the aggressor but also exacerbate the vulnerability of victims by creating a sustained and pervasive impact.

Figure 1. Enhanced Cyberbullying Power Imbalance Model, incorporating the role of information misuse and technological literacy in cyberbullying dynamics

A key addition to the model is the concept of information misuse, which represents acts such as unauthorized access, manipulation, or dissemination of private content. Cyberbullies frequently weaponize information to undermine their victims’ psychological well-being and social standing. Examples include the sharing of sensitive photos, creation of fake profiles, or spreading defamatory material. These actions exemplify how the digital environment reshapes traditional power dynamics, allowing aggressors to assert dominance while evading accountability (Spyropoulos, 2011; Katerelos et al., 2011).

The systematic abuse of information is further reinforced by disparities in technological knowledge and familiarity with technology. Aggressors often possess advanced skills that allow them to exploit digital tools with greater precision, while victims, particularly those with limited digital literacy, are left unable to respond effectively. This knowledge gap deepens the power imbalance, making victims feel isolated and disempowered (Vandebosch & Van Cleemput, 2008; Ybarra & Mitchell, 2004a, 2004b).

These dynamics are supported by Gibson’s (2014) Theory of Affordances, which explains how digital tools shape user behavior. In cyberbullying, technological affordances such as anonymity and the scalability of harm allow aggressors to act with impunity, amplifying the psychological and social damage inflicted on victims (Topcu-Uzer & Tanrıkulu, 2018). For instance, the widespread availability of platforms like social media enables perpetrators to reach larger audiences while shielding themselves from detection.

At a macro level, this power imbalance is linked to broader structural factors. Socio-economic disparities often determine access to technological expertise, reinforcing systemic inequalities. Those in privileged positions are more likely to acquire advanced knowledge and resources, enabling them to manipulate information as a tool of control and dominance. This dynamic is mirrored in larger phenomena, such as political cyberbullying, cyberterrorism, and information warfare, where control over technology and data is central to power struggles (Millard, 2009; Zannis, 2005; Bosworth et al., 1999).

The “Enhanced Cyberbullying Power Imbalance Model” underscores the interplay between these individual and systemic factors. It illustrates how aggressors leverage technological tools and knowledge gaps to consolidate their dominance, making interventions particularly challenging. The model calls for targeted strategies that address these imbalances at both individual and structural levels (Figure 1).

So, the systematic misuse of information is at the heart of the power imbalance inherent in cyberbullying. This phenomenon is driven not only by individual behavior but also by technological and systemic factors that reshape traditional notions of harm and control. Addressing this issue requires a multifaceted approach. Interventions must focus on bridging gaps in digital literacy, empowering victims with resilience, and fostering greater accountability among platforms. Moreover, promoting equitable access to technology and implementing robust ethical and legal safeguards are critical to rebalancing the dynamics of power in the digital sphere. By integrating these strategies, stakeholders can work toward a safer, more equitable, and inclusive digital environment.

2. Cyberbullying and Technoethics: A Technoethical Flow Analysis

Cyberbullying constitutes not only a sociotechnical phenomenon but also a fundamental ethical challenge in the digital age. As Luppicini (2018) observes, technoethics offers a conceptual lens through which we can examine the intersection of technology and human values, shedding light on the misuse of digital platforms for aggressive or harmful behaviors. Cyberbullying – defined as the intentional and repeated harm inflicted through digital devices – amplifies these concerns, as aggressors exploit affordances such as anonymity, virality, and permanence to target victims (Langos, 2012; Menesini et al., 2013).

The technoethical implications are manifold. Firstly, cyberbullying undermines the principle of digital dignity, defined as the right of individuals to exist in online spaces free from humiliation and harm (Verbeek, 2011). Platforms often fail to intervene effectively, despite possessing technological capabilities to moderate or flag harmful content4. This reveals a gap between technological potential and ethical implementation. As Moor (2005) argues, emerging technologies require evolving ethical frameworks – ones that anticipate misuse and promote societal well-being.

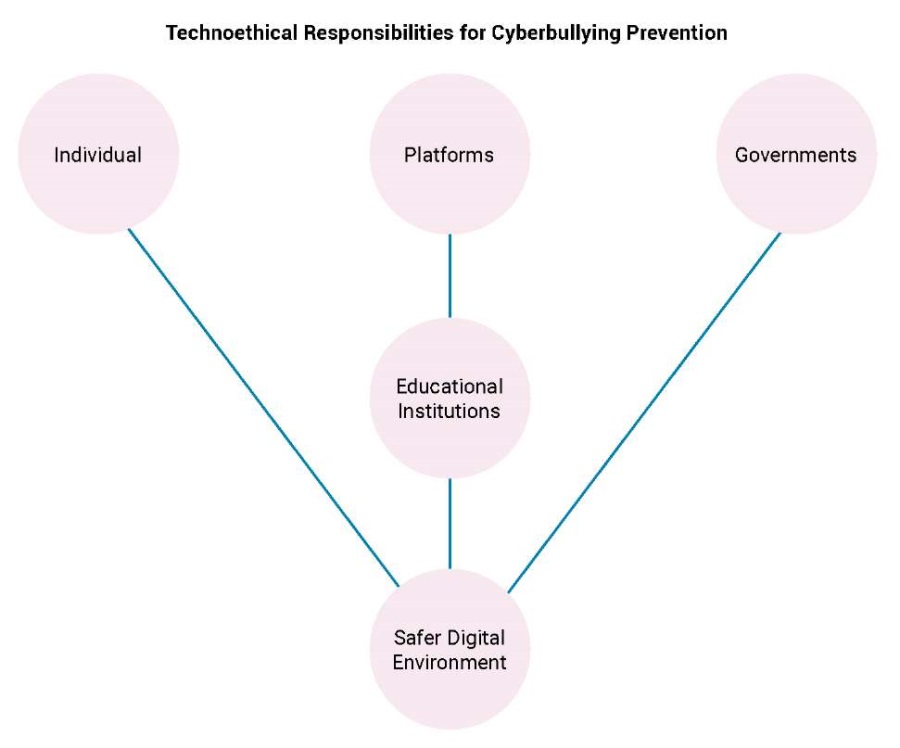

Secondly, cyberbullying highlights power imbalances embedded in digital infrastructures. The capacity to harm is not evenly distributed; aggressors often possess greater technological fluency, while victims may lack digital literacy or access to effective reporting mechanisms (Spyropoulos, 2011; Katerelos et al., 2011). These asymmetries, visualized in the Technoethical Responsibilities Flowchart (Figure 2), offer a structured mapping of responsibility across multiple actors.

Figure 2. Technoethical Responsibilities Flowchart, highlighting the collaborative roles of individuals, platforms, governments, and educational institutions in addressing cyberbullying

This conceptual tool identifies four primary layers of responsibility:

- Design-Level Responsibility: At the foundational level lie system designers and developers. Their choices in platform architecture, moderation features, and affordances shape user interactions. If anonymity is permitted without safeguards, or if virality is incentivized without accountability, then cyberbullying becomes more likely (Capurro, 2009; Tavani, 2011).

- Operational Responsibility: Platform operators and content moderators are ethically obligated to monitor, detect, and remove harmful content, while preserving freedom of expression. Failure to act promptly or transparently exacerbates victimization (Zuboff, 2019).

- User-Level Responsibility: Ethical conduct is not the sole burden of institutions. Users must exercise empathy, restraint, and digital citizenship. Educational programs targeting youth can instill these technoethical values (Chen, 2017; Ortega-Ruiz et al., 2012).

- Regulatory-Level Responsibility: While not extensively addressed here, frameworks such as the GDPR enforce transparency, accountability, and user rights, embodying technoethical norms in legal terms5. These frameworks are examined in greater detail in subsequent sections.

The flowchart illustrates that technoethical responsibility in cyberbullying contexts is not linear but distributed and interdependent. No single stakeholder can resolve the issue in isolation. The strength of technoethical analysis lies in emphasizing this interconnectedness.

Moreover, automation and AI-based detection tools introduce new layers of complexity. While such systems may identify patterns of abuse, they can also reproduce bias or fail to grasp contextual nuance (Ioannou et al., 2018). Therefore, transparency and human oversight remain indispensable (Tavani, 2011).

In sum, cyberbullying – when viewed through a technoethical framework – reveals the necessity for shared responsibility, ethical system design, proactive intervention, and the cultivation of respect for digital dignity across all levels of the sociotechnical ecosystem.

3. The Nexus Between Technoethics, Cyberbullying, and Its Prevention

Technoethics provides a critical framework for examining the ethical dimensions of cyberbullying, offering a robust foundation for the development of policies and strategies to mitigate its impact. By focusing on the shared responsibilities of individual users, technological platforms, and regulatory bodies, technoethics advocates for a safer, more equitable digital environment. The prevention and management of cyberbullying require a comprehensive approach that goes beyond the application of technological solutions or isolated legislative measures. Importantly, most of these prevention frameworks are deeply rooted in psychological science, emphasizing emotional resilience, empathy-building, and behavioral awareness. Thus, effective intervention must integrate ethical principles, educational initiatives, and innovative psychosocial strategies to ensure that technological progress aligns with human rights and societal well-being (Hinduja & Patchin, 2009).

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) constitutes one of the most significant legal instruments for safeguarding personal data within the European Union6, particularly in contexts of online harm. By enshrining principles such as data minimization and the right to erasure, it empowers victims of cyberbullying to reclaim control over their digital presence and seek redress against the misuse of personal information. More than a regulatory mechanism, the GDPR embodies core technoethical values – transparency, accountability, and autonomy – transforming digital rights into enforceable ethical protections. In doing so, it contributes to a more respectful and human-centered digital environment7.

Equally critical is the Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act), introduced by the European Union as the first comprehensive global framework to regulate AI technologies (Regulation (EU) 2024/1689). The AI Act employs a risk-based approach to classify AI systems, ranging from minimal to high risk. Tools used for content moderation and the detection of harmful online behaviors, such as cyberbullying, are typically categorized as high-risk systems, necessitating strict compliance with transparency, fairness, and oversight requirements. These obligations ensure that AI systems employed on social media platforms or in educational settings are accurate, impartial, and supervised by human operators. Furthermore, the AI Act prohibits manipulative technologies that could influence user behavior in harmful ways, reflecting its commitment to safeguarding user rights while promoting ethical innovation.

At the international level, the United Nations Convention against Cybercrime, adopted in 2024, represents a significant milestone in addressing ICT-facilitated crimes. While the convention provides a comprehensive framework for combating cybercrime, including illegal system access, data breaches, and online fraud, it notably excludes explicit provisions for cyberbullying. This omission highlights the ongoing challenges in achieving a unified global approach to addressing this widespread issue. Despite this gap, several provisions within the convention have indirect relevance to cyberbullying. For instance, Article 14 addresses online child sexual abuse, and Article 16 targets the unauthorized dissemination of intimate images, behaviors often associated with cyberbullying. Furthermore, Article 18 establishes the liability of platforms that facilitate harmful activities, while Article 34 includes measures for victim assistance and protection8.

The absence of explicit references to cyberbullying within the United Nations Convention against Cybercrime9. Underscores the need for further amendments or supplementary protocols. A harmonized international framework addressing cyberbullying is essential to bridge this gap, especially given the transnational nature of many incidents. Victims of cyberbullying often face significant barriers to justice when perpetrators operate across jurisdictions. Establishing a universal definition of cyberbullying would provide a foundation for coordinated efforts, enabling clearer pathways for legal action and victim support. In addition, aligning the convention with technoethical principles could enhance its applicability, ensuring that regulatory measures reflect the ethical imperatives of fairness, accountability, and user protection.

Despite these limitations, the convention serves as an important step toward global collaboration on cyber-related crimes. Its emphasis on cross-border cooperation and its focus on shared responsibilities among member states create a framework that could be adapted to address the unique challenges of cyberbullying. As digital platforms continue to evolve, the inclusion of cyberbullying-specific provisions in future revisions of the convention would strengthen its relevance and effectiveness.

By integrating technoethical principles into regulatory innovations such as the GDPR, AI Act, and United Nations Convention against Cybercrime (United Nations General Assembly, 2024), stakeholders can create a digital ecosystem that prioritizes safety, accountability, and inclusivity. Collaboration between governments, platforms, and civil society organizations is essential for developing cohesive strategies that align with ethical imperatives. For instance, partnerships with researchers and policymakers could facilitate the design of advanced tools for harm detection and mitigation. Furthermore, promoting best practices, such as transparency reports and algorithm audits, can ensure that platforms operate in ways that are both ethical and effective.

4. Practical and Interdisciplinary Recommendations

4.1. Technological Tools

The role of technology in preventing and managing cyberbullying has become increasingly significant, with modern platforms adopting innovative solutions to address harmful online behaviors. Μajor platforms, employ advanced artificial intelligence (AI) tools to detect and remove harmful content. According to Meier et al. (2016), AI systems are particularly effective in real-time monitoring, identifying suspicious behavior, and mitigating the spread of offensive posts. For instance, automated reporting systems can significantly reduce victims’ exposure to abusive comments by flagging and removing harmful content promptly.

However, while AI offers powerful tools for moderating harmful content, it is not without limitations. As Zuckerberg10 noted, AI systems struggle to understand complex contexts and cultural nuances, making them less effective in situations requiring subtle judgment. A hybrid approach that combines AI technology with human oversight is essential to ensure accuracy and fairness in content moderation. This perspective aligns with Zuckerberg’s11 emphasis on collective user involvement through tools like Community Notes, which empower users to contribute context and collaboratively address misleading information or harmful content.

From a technoethical standpoint, the deployment of surveillance and monitoring technologies in combating cyberbullying must balance safety with privacy. Floridi (2014) argues that transparency, respect for individual rights, and robust data protection are vital to avoiding oppressive practices. The ethical use of technology requires systems that prioritize human dignity while delivering effective solutions to reduce online harm.

In addition to advancing technological tools, the need for multi-stakeholder collaboration is paramount. Governments, civil society, and technology platforms must co-develop content moderation protocols that balance effectiveness with fairness. These collaborations should focus on creating transparent systems that prioritize harm prevention while safeguarding user rights. By pooling expertise and resources, stakeholders can develop adaptable and culturally sensitive solutions to address the complexities of cyberbullying across diverse digital environments.

Partnerships with educational institutions further enhance the efficacy of prevention strategies. Schools and universities can integrate digital ethics and resilience training into their curricula, equipping students with the skills needed to navigate digital spaces safely and responsibly. These programs should emphasize critical thinking, empathy, and digital literacy, fostering a culture of respect and accountability among younger generations. Collaborative initiatives between educators, policymakers, and platforms can create comprehensive educational frameworks that address the root causes of cyberbullying while promoting ethical digital behavior.

By combining technological innovation with ethical principles and interdisciplinary collaboration, stakeholders can address the complexities of cyberbullying effectively. This approach not only mitigates harm but also upholds the broader principles of fairness, accountability, and respect for human dignity, ensuring that technological progress aligns with societal values.

4.2. Digital Citizenship and Promoting Responsible Behavior

Technoethics highlights the vital importance of fostering digital citizenship, advocating for the cultivation of responsible and respectful behavior in online interactions. Education in digital citizenship encompasses essential principles such as demonstrating respect for others, upholding a sense of accountability in virtual environments, and refraining from harmful behaviors, including cyberbullying. The promotion of these values is integral to the prevention of online misconduct, as it strengthens social responsibility and fosters a culture of respect within the broader digital and educational environment12.

4.3. Protection of Victims

The effective protection of victims of cyberbullying requires the establishment of structured and victim-centered reporting frameworks. Such frameworks should enable secure and confidential reporting of incidents, ensuring victims feel safe, supported, and empowered throughout the process. Transparency and trust are critical in managing complaints effectively, fostering an environment where individuals are confident in seeking help. From a technoethical perspective, technological tools must prioritize victim welfare, integrating features that enhance safety and provide accessible avenues for reporting and support.

Confidential and secure reporting channels are essential for achieving these objectives. Educational institutions and communication platforms can play a pivotal role by implementing systems that allow students and users to report bullying or harassment without fear of retaliation or exposure. These channels should be designed to offer anonymity and user protection while ensuring swift and effective resolution. For instance, Ioannou et al. (2018) highlight the importance of integrating such tools into school networks and digital platforms, reinforcing the ethics of care in both educational and online environments.

To complement these frameworks, governments should consider funding dedicated cyberbullying hotlines. These hotlines would provide victims with immediate access to psychological support and guidance, connecting them with trained professionals who can offer advice and assistance tailored to their needs. Such initiatives can bridge critical gaps in victim support, particularly in cases where individuals may lack access to other resources. By addressing the psychological and emotional dimensions of cyberbullying, these hotlines contribute to the holistic protection of victims and the promotion of mental well-being.

In addition to reactive measures, a proactive approach to victim protection can be achieved through the development of a Digital Resilience Index. This tool would assess the capacity of vulnerable groups, such as children and adolescents, to navigate cyber risks safely and effectively. The index could evaluate factors such as digital literacy, emotional resilience, and access to support systems, providing valuable insights into the specific needs of at-risk populations. By identifying areas for improvement, the Digital Resilience Index can guide targeted interventions, including education, awareness campaigns, and policy adjustments.

Such victim-centered strategies not only mitigate the immediate impacts of cyberbullying but also foster a culture of empathy and support within digital and educational spaces. Tavani (2011) emphasizes that prioritizing victim welfare and cultivating a sense of safety are integral to building resilience and empowering individuals to reclaim control over their digital experiences. Collaborative efforts among governments, platforms, and civil society organizations are crucial in ensuring these frameworks are both effective and widely accessible.

By integrating secure reporting channels, government-funded support services, and tools like the Digital Resilience Index, stakeholders can create a comprehensive system for victim protection. These measures, grounded in technoethical principles, address the multifaceted challenges of cyberbullying while promoting a more inclusive and supportive digital environment.

4.4. Ethical Dilemmas

The use of technology to prevent cyberbullying, while yielding significant benefits, raises complex ethical and legal dilemmas that demand careful examination. One key issue is the protection of privacy, particularly in the context of data surveillance practices employed by social media platforms. These practices aim to identify suspicious behavior and prevent cyberbullying but carry the inherent risk of abuse of power. The collection and analysis of large datasets, often conducted without explicit user consent, can lead to potential violations of privacy rights and personal autonomy, as protected under frameworks like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This raises critical questions about the extent to which privacy can be compromised to ensure online safety.

Another pressing concern involves the deployment of content moderation algorithms. While these tools are designed to detect and remove harmful content, they often lack the nuance to distinguish between hate speech and lawful expressions of sarcasm or criticism. Such limitations can result in unintended censorship, restricting freedom of expression, a right enshrined in international agreements such as the European Convention on Human Rights (Article 10 ECHR)13. This scenario undermines the democratic exchange of ideas and highlights the need for safeguards to prevent overreach.

These dilemmas underscore the necessity of balancing the rights to privacy and freedom of expression with the imperative to protect user safety and dignity. Technoethics offers a framework for addressing these challenges by promoting transparency in surveillance practices and ensuring accountability in the design and implementation of content moderation algorithms. Establishing such frameworks can prevent abuses, foster trust in digital platforms, and ensure that technological interventions respect fundamental rights while enhancing online safety.

4.5. Strengthening Collaboration and Data-Driven Insights

The transnational nature of cyberbullying necessitates a unified and collaborative global response. Due to its ability to transcend national borders, cyberbullying challenges traditional jurisdictional boundaries and requires harmonized legal frameworks to ensure consistent protections for victims worldwide. The decentralized structure of the internet often allows perpetrators to exploit disparities in national laws, making international cooperation imperative. A global approach grounded in shared principles of justice, accountability, and human rights is necessary to address these challenges effectively.

A key recommendation is the establishment of an International Cyberbullying Prevention Taskforce, which would facilitate cross-border investigations, enable information sharing, and support coordinated law enforcement efforts. This body could bridge jurisdictional gaps by developing internationally recognized protocols for handling cyberbullying cases and ensuring that perpetrators face accountability regardless of geographic location. Additionally, it could work toward the harmonization of national legal frameworks with international standards, reducing policy fragmentation and ensuring victims receive equitable legal protections.

At the policy level, several national initiatives demonstrate promising approaches to addressing cyberbullying. Countries have implemented diverse strategies, ranging from digital literacy campaigns and technological tools to specialized legal frameworks that recognize the unique harm inflicted by online aggression. For example, Greece has introduced the «Safe Youth» digital application14, an innovative tool designed to support minors aged 12 and older in addressing online threats. This application provides direct communication with emergency services, discreet emergency notifications for real-time threats, and a secure system for submitting abuse reports through the Unified Digital Portal of Public Administration. By prioritizing accessibility, confidentiality, and immediacy, the Safe Youth initiative represents a technoethical approach to digital safety, empowering minors to navigate crises safely. However, ensuring equitable access to this tool – particularly for marginalized populations or those with limited technological literacy – remains a critical challenge.

Despite the progress of national initiatives like Safe Youth, a significant challenge in existing legal frameworks is their adaptability to emerging technological threats. Many laws focus on traditional online harassment mechanisms but fail to account for algorithm-driven amplification of harmful content, misuse of artificial intelligence (AI), and the role of digital anonymity in perpetuating abuse. Future regulatory frameworks must address these evolving dynamics, particularly regarding social media algorithms, gaming platforms, and AI-generated content (e.g., deepfakes). Expanding legal protections to cover these areas is crucial to maintaining the relevance and effectiveness of legislative measures.

From a criminological perspective, cyberbullying reflects an imbalance of power, where perpetrators leverage anonymity and the expansive reach of digital platforms to act with impunity. While legal accountability mechanisms provide recourse for victims, long-term cultural and systemic shifts are needed to address the broader social structures that enable digital aggression. Integrating restorative justice principles (Guardabassi & Nicolini, 2024; Duncan, 2016), rehabilitation programs for offenders (Othman et al., 2024), and sustained victim support systems can contribute to a more holistic approach to prevention and intervention (Vandebosch, 2019).

In parallel with legal and institutional responses, the integration of data-driven insights is critical for understanding cyberbullying trends and designing effective interventions. Conducting meta-analyses on the prevalence of cyberbullying and examining platform-specific risk factors can help policymakers and researchers develop targeted prevention strategies (Sathya & Fernandez, 2024; Kim et al., 2021). For instance, studying how algorithms amplify harmful content or how anonymous features facilitate harassment can provide valuable insights into mitigating the negative impact of these technologies (Johora et al., 2024; Meier et al., 2016).

Furthermore, anonymized data-sharing agreements between digital platforms and research institutions represent a promising avenue for combating cyberbullying. Social media platforms collect vast amounts of behavioral data that, when responsibly anonymized, could be leveraged to identify patterns of abuse and develop proactive solutions. Transparent agreements that balance privacy rights with research accessibility can foster innovation while protecting individual users (Floridi, 2014).

By strengthening international collaboration, refining national legal frameworks, and leveraging data-driven insights, stakeholders can build a cohesive, global strategy to combat cyberbullying. Initiatives like Greece’s Safe Youth demonstrate the potential of digital tools in mitigating online threats, but they must be complemented by comprehensive international efforts. Integrating technoethical principles – which prioritize accountability, digital rights, and equitable access to protection mechanisms – will be key in fostering a safer, more inclusive, and resilient digital environment for future generations.

Conclusions

Cyberbullying, as a pervasive form of digital aggression, exemplifies the misuse of technology to harm, intimidate, or humiliate individuals. Addressing this multifaceted issue demands a holistic approach that integrates prevention, legal mechanisms, technological innovation, and ethical considerations. Central to these efforts is the recognition of structural inequities, such as disparities in technological access and literacy, which amplify vulnerabilities and perpetuate power imbalances in digital interactions (Lazos, 2001). Empowering users with knowledge and fostering an ethical culture of information usage remain crucial steps toward promoting responsible engagement in digital environments (Tsouramanis, 2005).

Policy recommendations must emphasize adaptive and forward-looking legal frameworks at both national and international levels. Governments should collaborate to harmonize laws addressing cyberbullying, ensuring consistency and accountability across jurisdictions. The establishment of an International Cyberbullying Prevention Taskforce, as well as a Global Cyberbullying Prevention Treaty, would strengthen cross-border investigations and provide unified standards for combating this issue. These frameworks must be dynamic, incorporating emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, blockchain, and algorithmic transparency, which play a dual role in enabling and preventing harm.

Collaboration among stakeholders is essential for creating a comprehensive response. Technology platforms bear a critical responsibility to design and implement robust content moderation systems, transparency mechanisms, and user protection measures. Governments must legislate adaptive laws that balance individual freedoms with protections against online harm. Civil society organizations and educational institutions also play pivotal roles in shaping ethical norms, promoting awareness, and providing support for victims.

Prevention remains the cornerstone of addressing cyberbullying. Educational institutions should integrate digital literacy, resilience-building, and ethical technology use into curricula, empowering students to navigate online spaces responsibly. Government-funded awareness campaigns and parental engagement initiatives should complement these efforts, fostering a culture of empathy and accountability. Moreover, bridging the digital divide and promoting equitable access to technology are critical for addressing systemic inequities that exacerbate cyberbullying. Ensuring all users – particularly vulnerable groups – have the tools and knowledge to engage safely in digital spaces aligns with the ethical imperatives of inclusivity and social justice.

Ethical dilemmas persist in the implementation of technological tools, such as AI-driven content moderation and surveillance technologies, which must balance effectiveness with respect for privacy and human dignity. The principles of technoethics – responsibility, accountability, and inclusivity – must guide these innovations to ensure they align with societal well-being rather than perpetuate harm.

In conclusion, combating cyberbullying requires a multidisciplinary, collaborative approach that integrates policy innovation, stakeholder engagement, and ethical foresight. By addressing root causes, promoting equitable access, and fostering a culture of responsibility, society can mitigate the harms of cyberbullying. Such efforts ensure that technological advancements contribute to the creation of a safer, more inclusive digital ecosystem, where the rights, dignity, and well-being of all users are prioritized.

1. UNICEF, n.d. Cyberbullying: What is it and how to stop it. https://clck.ru/3NQaBe

2. European Commission. (2009). Safer Internet Programme: Protecting children online. https://clck.ru/3NQaRi

3. United Nations. (2016). Ending the Torment: Tackling Bullying from Schoolyard to Cyberspace. https://clck.ru/3NQaWz; United Nations. (2016). Convention on the Rights of the Child: General Comment No. 20 (2016) on the Implementation of the Rights of the Child during Adolescence (CRC/C/GC/20). https://clck.ru/3NQaZ3

4. Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2014). Cyberbullying: Identification, Prevention and Response. Cyberbullying Research Center. https://clck.ru/3NQcNU

5. European Parliament and Council of the European Union. (2016). Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (General Data Protection Regulation). Official Journal of the European Union, L119, 1–88. https://clck.ru/3NQbz7

6. Ibid.

7. European Parliament and Council of the European Union. (2022). Directive (EU) 2022/2555 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 on measures for a high common level of cybersecurity across the Union, amending Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 and Directive (EU) 2018/1972, and repealing Directive (EU) 2016/1148. Official Journal of the European Union, L333, 80–137. https://clck.ru/3QGqvZ

8. United Nations General Assembly. (2024). United Nations Convention against Cybercrime: Strengthening international cooperation for combating crimes committed via ICT systems and evidence sharing. https://clck.ru/3NQc2k

9. Ibid.

10. Zuckerberg*, M. (2024). It’s time to get back to our roots around free expression. Facebook Watch. https://clck.ru/3NQcAk (* A co-founder of Meta , a company banned in the Russian Federation and included in the list of extremist organizations.)

11. A co-founder of Meta, a company banned in the Russian Federation and included in the list of extremist organizations.

12. Bynum, T. W. (2008). Computer and Information Ethics. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://clck.ru/3NQcEy

13. Council of Europe. (1950). European Convention on Human Rights, Article 10: Freedom of Expression. https://clck.ru/3NQngR

14. Ministry of Citizen Protection, Hellenic Police and Vodafone Foundation. (2024). SAFE.YOUth: Digital Application for the Protection of Minors. https://clck.ru/3NQcsT

References

1. Bosworth, K., Espelage, D. L., & Simon, T. R. (1999). Factors associated with bullying behavior in middle school students. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 19(3), 341–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431699019003003

2. Chakraborty, S., Bhattacherjee, A., & Onuchowska, A. (2021). Cyberbullying: A review of the literature. SSRN. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3799920

3. Campbell, M., & Bauman, S. (2018). Cyberbullying: Definition, consequences, prevalence. In M. Campbell & S. Bauman (Eds.), Reducing Cyberbullying in Schools (pp. 3–16). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-811423-0.00001-8

4. Capurro, R. (2009). Digital ethics. The Information Society, 25(3), 183–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972240902848902

5. Chen, C. W. Y. (2017). “Think before you type”: The effectiveness of implementing an anti-cyberbullying project in an EFL classroom. Pedagogies, 13(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554480X.2017.1363046

6. Courakis, N. (2005). Criminological horizons. Vol. II: Pragmatic approach and individual issues. 2nd ed. Athens – Komotini: Ant. N. Sakkoula (In Greek).

7. Duncan, S. H. (2016). Cyberbullying and restorative justice. In R. Navarro, S. Yubero & E. Larrañaga (Eds.). Cyberbullying Across the Globe (pp. 239–257). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

8. Englander, E., Donnerstein, E., Kowalski, R., Lin, C. A., & Parti, K. (2017). Defining cyberbullying. Pediatrics, 140(Supplement_2), S148–S151. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1758u

9. Floridi, L. (2014). The Fourth Revolution: How the Infosphere is Reshaping Human Reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

10. Furnell, S. M. (2006). Computer Insecurity: Risking the System. Oxford: Chandos Publishing.

11. Gibson, J. J. (2014). The theory of affordances (originally published 1979). In G. Bridge & S. Watson (Eds.). The People, Place, and Space Reader (pp. 56–60). London: Routledge.

12. Guardabassi, V., & Nicolini, P. (2024). Adolescence and cyberbullying: a restorative approach. In INTED2024 Proceedings (pp. 4562–4570). IATED. https://doi.org/10.21125/inted.2024.1183

13. Hasan, M. T., Hossain, M. A. E., Mukta, M. S. H., Akter, A., Ahmed, M., & Islam, S. (2023). A review on deep-learning-based cyberbullying detection. Future Internet, 15(5), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi15050179

14. Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2006). Bullies move beyond the schoolyard: A preliminary look at cyberbullying. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 4(2), 148–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204006286288

15. Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2009). Bullying beyond the schoolyard: Preventing and responding to cyberbullying. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

16. Ioannou, A., Blackburn, J., Stringhini, G., De Cristofaro, E., Kourtellis, N., & Sirivianos, M. (2018). From risk factors to detection and intervention: a practical proposal for future work on cyberbullying. Behaviour & Information Technology, 37, 258–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2018.1432688

17. Johora, F. T., Khan, M. S. I., Kanon, E., Rony, M. A. T., Zubair, M., & Sarker, I. H. (2024). A data-driven predictive analysis on cyber security threats with key risk factors. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.00068.

18. Juvonen, J., & Gross, E. F. (2008). Extending the school grounds? Bullying experiences in cyberspace. Journal of School Health, 78(9), 496–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00335.x

19. Katerelos, I., Tsekeris, C., Lavdas, M., & Demetriou, K. (2011). A psychosociological approach to Internet use and mass online role-playing games. In K. Siomos & G. Floros (Eds.), Research, prevention, management of risks in Internet use. Larissa: Hellenic Society for the Study of Internet Addiction Disorder. (In Greek).

20. Kim, S., Razi, A., Stringhini, G., Wisniewski, P. J. and De Choudhury, M. (2021). A human-centered systematic literature review of cyberbullying detection algorithms. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5(CSCW2). https://doi.org/10.1145/3476066

21. Kowalski, R. (2018). Cyberbullying. In J. P. Forgas, R. F. Baumeister & T. F. Denson (Eds.), The Routledge International Handbook of Human Aggression (pp. 131–142). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315618777-11

22. Langos, C. (2012). Cyberbullying: The challenge to define. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15(6), 285–289. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0588

23. Lazos, G. (2001). Information Technology and Crime. Athens: Nomiki Bibliothiki. (In Greek).

24. Li, Q. (2007). New bottle but old wine: A research of cyberbullying in schools. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(4), 1777–1791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2005.10.005

25. Luppicini, R. (2018). The Changing Scope of Technoethics in Contemporary Society. Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-5094-5

26. Meier, A., Reinecke, L., & Meltzer, C. E. (2016). “Facebocrastination”? Predictors of using Facebook* for procrastination and its effects on students’ well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.011

27. Menesini, E., Nocentini, A., & Palladino, B. E. (2012). Empowering students against bullying and cyberbullying: Evaluation of an Italian peer-led model. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 6(2), 313–320. https://doi.org/10.4119/ijcv-2922

28. Menesini, E., Nocentini, A., & Camodeca, M. (2013). Morality, values, traditional bullying, and cyberbullying in adolescence. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 31(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835X.2011.02066.x

29. Millard, G. (2009). Stephen Harper and the politics of the bully. Dalhousie Review, 89(3), 329–336.

30. Moor, J. H. (2005). Why we need better ethics for emerging technologies. Ethics and Information Technology, 7(3), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-006-0008-0

31. Mouzaki, D. (2010). International scientific conference on: “Dealing with cyberbullying from a legal perspective”. The Art of Crime, 15. (In Greek).

32. Nocentini, A., Calmaestra, J., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Scheithauer, H., Ortega, R., & Menesini, E. (2010). Cyberbullying: Labels, behaviours and definition in three European countries. Australian Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 20(2), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1375/ajgc.20.2.129

33. Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at School: What We Know and What We Can Do. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

34. Ortega-Ruiz, R., Del Rey, R., & Casas, J. A. (2012). Knowing, building and living together on internet and social networks: the ConRed cyberbullying prevention program. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 6(2), 303–313. https://doi.org/10.4119/ijcv-2921

35. Othman, S. N., Alziboon, M. F., Dawood, M., Sachet, S. J., & Moroz, I. (2024). New rehabilitation against electronic crimes by young people. Encuentros: Revista de Ciencias Humanas, Teoría Social y Pensamiento Crítico, 22, 363–385. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13732745

36. Raj, M., Singh, S., Solanki, K., & Selvanambi, R. (2022). An application to detect cyberbullying using machine learning and deep learning techniques. SN Computer Science, 3(5), 401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-022-01266-w

37. Sathya, J., & Fernandez, F. M. H. (2024). Predictive analysis in healthcare systems. In A. J. Anand, K. Kalaiselvi & J. M. Chatterjee (Eds.), Artificial Intelligence – Based System Models in Healthcare (pp. 131–152). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781394242528.ch6

38. Slonje, R., & Smith, P. K. (2008). Cyberbullying: Another main type of bullying? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 49(2), 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00611.x

39. Smith, P. K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(4), 376–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x

40. Smith, P. K., del Barrio, C., & Tokunaga, R. S. (2013). Definitions of bullying and cyberbullying: How useful are the terms? In S. Bauman, D. Cross & J. Walker (Eds.), Principles of cyberbullying research: Definitions, measures, and methodology (pp. 26–40). New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

41. Spyropoulos, F. (2011). The manifestations of deviant behavior on the Internet – Reflections on the needs of modernization of Greek criminal legislation. In K. Siomos & G. Floros (Eds.), Research, Prevention, Management of Risks in Internet Use. Larissa: Hellenic Society for the Study of Internet Addiction Disorder. (In Greek).

42. Tavani, H. T. (2011). Ethics and Technology: Controversies, Questions, and Strategies for Ethical Computing (3rd ed). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

43. Topcu-Uzer, C., & Tanrıkulu, İ. (2018). Technological solutions for cyberbullying. In M. Campbell & S. Bauman (Eds.), Reducing cyberbullying in schools (pp. 33–47). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-811423-0.00003-1

44. Tsouramanis, Ch. (2005). Digital Crime – The (Un)Safe Side of the Internet. Athens: V. Katsaros Publications. (In Greek).

45. Vandebosch, H. (2019). Cyberbullying prevention, detection and intervention. In W. Heirman, M. Walrave & H. Vandebosch (Eds.), Narratives in Research and Interventions on Cyberbullying among Young People (pp. 29–44). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04960-7_3

46. Vandebosch, H., & Van Cleemput, K. (2008). Defining cyberbullying: A qualitative research into the perceptions of youngsters. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 11(4), 499–503. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.0042

47. Verbeek, P.-P. (2011). Moralizing Technology: Understanding and Designing the Morality of Things. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226852904.001.0001

48. Ybarra, M. L., & Mitchell, K. J. (2004a). Online aggressors/targets, aggressors, and targets: A comparison of associated youth characteristics. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 1308–1316. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00328.x

49. Ybarra, M. L., & Mitchell, K. J. (2004b). Youth engaging in online harassment: Associations with caregiver-child relationships, Internet use, and personal characteristics. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.03.007

50. Zannis, A. (2005). Cybercrime. Athens-Komotini: Sakkoulas Publications. (In Greek).

51. Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: PublicAffairs.

About the Author

Fotios SpyropoulosCyprus

Fotios Spyropoulos – PostDoc, PhD, Associate Professor of Criminal Law & Criminology, Faculty of Law; Senior Partner

4-6 Lamias Street, 2001, P.O. Box 28008, Nicosia, Cyprus;

Alexandras Avenue 81, 11474, Athens, Greece

Google Scholar ID: iKQYLWoAAAAJ.

Competing Interests:

The author declares no conflict of interest.

- An expanded model of the power imbalance in cyberbullying was developed, including factors of technological literacy and information abuse as key mechanisms for systematic harm in the digital environment;

- A pattern for the distribution of techno-ethical responsibility was proposed, defining four levels of responsibility: design, platform operators, users and legislative regulation;

- The digital sustainability index was proposed as a tool for assessing the ability of vulnerable groups to cope with cyber risks and for developing targeted educational programs;

- The author developed recommendations on the ethical use of artificial intelligence systems in content moderation to ensure a balance between user safety and freedom of expression.

Review

For citations:

Spyropoulos F. Techno-Ethical and Legal Aspects of Cyberbullying: Structural Analysis of Power Imbalances in the Digital Sphere. Journal of Digital Technologies and Law. 2025;3(3):472-496. https://doi.org/10.21202/jdtl.2025.19. EDN: bvlgsu