Scroll to:

Neurorights, Neurotechnologies and Personal Data: Review of the Challenges of Mental Autonomy

https://doi.org/10.21202/jdtl.2024.36

EDN: sperfj

Abstract

Objective: to present the results of a systematic review of research on the impact of neurotechnology on legal concepts and regulatory frameworks, addressing ethical and social issues related to the protection of individual rights, privacy and mental autonomy.

Methods: The systematic literature review was based on the methodology proposed by a renowned British scholar, a professor emerita of computer science at Keele University Barbara Kitchenham, chosen for its flexibility and effectiveness in obtaining results for publication. Thorough searches were carried out with the search terms “neurotechnology”, “personal data”, “mental privacy”, “neuro-rights”, “neurotechnological interventions”, and “neurotechnological discrimination” on both English and Spanish sites, using search engines like Google Scholar and Redib as well as databases including Scielo, Dialnet, Redalyc, Lilacs, Scopus, Medline, and Pubmed. The focus of this research is bibliometric data and its design is non-experimental with a cross-sectional and descriptive, using content analysis based on PRISMA model.

Results: the study emphasizes the need to establish clear ethical principles to protect individual rights and promote responsible use of neurotechnologies; a number of problems of mental autonomy were identified, such as improper handling of information, lack of legal security guarantees, violation of rights and freedoms in the medical sphere. The author shows the need to adapt the existing regulatory legal framework to address the ethical and social problems arising from the new neurotechnologies. It is noted that a broad study of neurotechnology issues will contribute to the protection of human rights.

Scientific novelty: an expanded understanding of the five neurorights within the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is proposed; neurorights are viewed as a new category of rights aimed at protecting mental integrity against the misuse of neurotechnologies. The author justifies the adoption of such technocratic principles as personal identity, free will, mental privacy, equal access and protection against bias.

Practical significance: the obtained results are relevant for understanding modern legal concepts related to neurorights and for adapting the existing normative legal acts to solve ethical and social problems arising from the emergence of new technologies, protection of human neurorights and liability for their violation. The study of these issues is key for provision of further responsible development and use of neurotechnologies.

Keywords

For citations:

Cornejo Y. Neurorights, Neurotechnologies and Personal Data: Review of the Challenges of Mental Autonomy. Journal of Digital Technologies and Law. 2024;2(3):711-728. https://doi.org/10.21202/jdtl.2024.36. EDN: sperfj

Introduction

The rapid advancement of neurotechnologies has opened up unprecedented possibilities for understanding and enhancing the functioning of the human brain. However, this progress has also posed significant ethical and social challenges related to the protection of individual rights, privacy, and mental autonomy.

In this context, there arises the need to establish a conceptual and practical framework to guide the responsible development and application of these technologies. Neurorights, as defined by Moisés Barrio, are the digital rights of citizens that can be exercised with the same effectiveness both within and outside the digital environment (Arellano, 2024; Parlatino, 2023; Fukushi, 2024).

In Spain, the Digital Rights Charter stands out as a fundamental element in recognizing rights in this environment, without replacing fundamental rights also known as human rights or individual guarantees. It is important to note that neurorights do not seek to create new fundamental rights, but rather to describe and specify the changing nature of the digital environment, thus proposing the recognition of new human rights to adapt to these changes (González, 2021; Hsu, 2024).

In the ethical and legal sphere, Goering et al. (2021) defines neurorights as “a conceptual and practical framework to guide the responsible development and application of neurotechnologies”, emphasizing the need to establish clear ethical principles that protect individual rights and promote the responsible use of these technologies (Gómez, 2021).

Meanwhile, Filipova (2022) describes them as “an emerging field that explores the ethical and legal challenges related to the development and application of neurotechnologies”, highlighting the importance of a solid regulatory framework to ensure the responsible development and application of these technologies (Cáceres & López, 2022).

Concerns about the potential ethical risks associated with neurotechnologies are shared by several authors. The creation of the Brain Activity Map (BAP) has sparked debates about mental privacy, the responsibility of our actions, and advances in neurotechnology, as well as issues of stigmatization and discrimination related to neurological measures. In this context, artificial intelligence, algorithmic biases, and neuroscientific evidence are relevant in legal and judicial domains (Fernández, 2023; López-Silva & Madrid, 2022; Cáceres et al., 2021; Clausen et al., 2017; Cornejo-Plaza et al., 2024).

Neurotechnologies have opened a world of possibilities for understanding and enhancing the functioning of the human brain, while posing ethical and social challenges related to the protection of individual rights, privacy, and mental autonomy. Hence, the research question arises: How can existing regulatory frameworks adapt to address the ethical and social challenges posed by emerging neurotechnologies? This question is pivotal to ensure the responsible development and application of neurotechnologies for the benefit of society.

The aim of this research is to conduct a bibliometric analysis of the effects of regulatory frameworks concerning the ethical and social challenges posed by emerging neurotechnologies for the betterment of humanity.

-

Neurorights, neurotechnologies and its legal and ethical implications

1.1. Neurorights

The field of neuro-rights emerges in response to the rapid development of neurotechnologies, which have the potential to transform how we understand and address the human brain. However, these technologies also pose significant ethical and social challenges related to the protection of individual rights, privacy, and mental autonomy (Moreu, 2022).

The earliest debates on neuro-rights trace back to the 1990s, with authors like Judy Illes, who began exploring the ethical implications of new brain technologies (Borbón & Borbón, 2022). In 2002, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) convened a conference on neuroethics, discussing the challenges and opportunities of neurotechnologies and proposing the need to develop an ethical framework for their development and application.

In this context, neuro-rights emerge as a conceptual and practical framework to address these challenges. The term “neuro-rights” constitutes a new category of rights aimed at protecting mental integrity from the misuse of neurotechnologies1.

Nonetheless, it is troubling that there isn’t a special international regulation in place to handle possible abuses of life, integrity, and freedom of speech resulting from multinational corporations trading in neurotechnologies (Parlatino, 2023).

López-Silva and Madrid (2022) are among the authors who demonstrate a strong connection between the terms “mental” and “psychic”, connecting them to the term “psychological”. Additionally, they suggest that “cerebral” be used in place of “neuronal,” given the strong connection between the two terms. In this sense, “mental” is closely linked to “mental privacy,” which is commonly used to refer to the confidentiality of neural information. But it’s crucial to understand that, depending on the application domain and the historical-cultural context of each scenario, the intricacy of this problem could evoke varied responses.

According to Parlatino (2023), neuro-rights, also known as brain rights, are a new international legal framework that emphasizes the protection of the brain and its functions in addition to the already established human rights. These rights include the right to one’s own identity, mental privacy, and individuality. Additionally, they incorporate materials with legally mandated safeguards to address the increasing hazards associated with the advancement and use of neurotechnologies in people (Moreu, 2022).

Neuroscientific research, therapeutic practice, and technology advancement are only a few of the many domains in which neuro-rights are applicable (Parlatino, 2023).

1.2. Neurotechnologies

Neurotechnologies refer to those technologies focused on the study of the improvement of the nervous system. Towards those parts that need rehabilitation or assistance due to loss of functions, that is, rehabilitation on motor disorders allows progress achieved in research and development in its most basic functions (Barrios et al., 2017).

Experts mention that neurotechnologies are related to a wide variety of methods and instruments that work in conjunction with the brain and nervous system in a general way and that monitor passively or alter the activity if it is active (Andorno, 2023).

Furthermore, report states that the benefits of neurotechnology are being explored in relation to the work environment by transcribing thoughts to screens without using keyboards, however, he is concerned about the implicit risks that may violate privacy, free will and human dignity.

UNESCO carried out a study where neurotechnology is only investigated in 10 Latin American countries, a situation that causes concern due to the possibility of little equitable access to knowledge and disparity in health care, research and innovation for the benefit of human beings2.

Neurotechnological research focused on the brain involves important challenges because it promotes the protection of neurorights aimed at legal reforms (Ruiz & Cayón, 2021) because methods and instruments are used to connect with the nervous system.

The use of neurotechnologies not only considers their therapeutic use but also their ability to stimulate the empowerment capabilities of human beings (Reguera & Cayón, 2021), the main concern of neurotechnology is its integration with AI because it can challenge the essence of the human being.

Likewise, neurotechnology exposes the intimacy of thoughts, emotions, subconscious as well as neuronal activity (Reguera & Cayón, 2021), but the concern of respect for human dignity, rights and fundamental freedoms, the latter due to the law on the protection of personal data, reoccurs. regulation already implemented in most countries around the world, as well as the confidentiality of mental data, personal identity, freedom of thought.

In fact, neurotechnologies related to neurorights are approached from two aspects: mental privacy and the right to privacy where the individuality of people is emphasized, which is why it is crucial that they be addressed by public powers at a regional and international level (Andorno, 2023).

In this way, neurotechnologies go beyond the medical field because they show us the opportunities and challenges in cognitive processes, being able to develop preventive and therapeutic diagnoses, and in that sense neurotechnologies have taken off at the level of Latam and the Caribbean where UNESCO has developed a series of studies that include the human genome together with artificial intelligence

Lately, neurotechnologies have made great advances because, due to big data, large volumes of data have been processed and, together with AI, results are obtained in a short time, allowing the identification of patterns of neural activity or thought reading, where the ethical and legal approach combines two categories: brain images (neuroimaging) and brain-computer interfaces (ICC, BCI) (Andorno, 2023).

1.3. Ethical and legal issues

The objective of neurotechnologies is to investigate neurological mechanisms of mental activity and human behavior to influence them, which leads to ethical and legal situations where they can be regulated according to values and principles of certain disciplines (Andorno, 2023), and for this reason, UNESCO expresses its concern about those groups that request the creation of new neurorights and that undermine the existing ones.

To understand these neurorights a little better, they are mentioned: mental privacy. Mental integrity, personal identity and cognitive freedom.

1.3.1. Mental Privacy

This right is closer to access to mental data that gives rise to neurotechnologies where an attempt is made to protect non-consensual access to your brain data by third parties, as well as the dissemination of the same, whether by advertising companies, insurers, employers, government companies, etc.

This respect is mentioned by international human rights standards that include the confidentiality of personal data, which states that there will be no arbitrary interference in the private life, family, home, honor or reputation of any person (art. 12), as well as supported by the American Convention on Human Rights of 1969 (known as the Pact of San José de Costa Rica) (Andorno, 2023).

However, there is concern that the protection of mental data due to a legal interpretation not provided for in the laws, which is why these regulations need to be clarified to ensure the privacy of said data and thus avoid dichotomies in the opinions of jurists (Reguera & Cayón, 2021; Hertz, 2022; Makin et al., 2020).

Finally, this mental information is of concern because it can be used as biometric data that identifies a person and can be used in the future for mental health issues and cognitive abilities for discrimination purposes (Arellano, 2024).

1.3.2. Mental Integrity

The confidentiality of mental data associated with neurotechnology applications can affect mental integrity due to the damage that could be caused to the psychological dimension of the person, due to the possible ease or access to intentionally alter the electrical stimulation parameters that can cause manipulating brain-computer interface devices. (Hertz, 2022; Alharbi, 2023).

Just as there are negative implications, there are also positive contributions in its use because the so-called “memory engineering” is used to treat diseases such as Alzheimer’s or post-traumatic stress, where they can erase memories that justify their disappearance for better mental health of the patient.

1.3.3. Personal Identity

Personal identity is related to the psychological continuity of an individual, whose own characteristics remain over time, being able to recognize themselves and differentiate themselves from others, that is, preserve their essence (Hertz, 2022).

When treatment therapies or procedures are performed that can alter your mental states, they could have consequences in possible changes in your behavior, this due to inappropriate or abusive use of brain stimulation devices, because we are subjects of rights that are protected by international standards.

1.3.4. Cognitive freedom

It is related to mental self-determination, that is, choosing and exercising control over one’s own mental states that can be altered or conditioned by third parties without their consent (Hertz, 2022).

The term freedom was used by Wrye Sententia in 2004 (Sententia, 2004), who explains that right and freedom are determined by one’s own conscience and thoughts, although Bublitz (Bublitz, 2013) explains that the right to alter and enhance one’s own mental states as well as to refuse the use of devices that can manipulate their mental states (Parlatino, 2023, Hertz, 2022).

Cognitive freedom is related to the freedom of thought recognized in Human Rights and it is imperative that it be clarified that said freedom also includes the internal dimension of mental activity (Andorno, 2023; Hertz, 2022).

-

Research methodology

The goal of the current study is to analyze the ethical and social issues surrounding neuro-rights in upcoming neurotechnologies through a thorough evaluation of the literature. Thorough searches were carried out using search engines like Google Scholar and Redib as well as databases including Scielo, Dialnet, Redalyc, Lilacs, Scopus, Medline, and Pubmed.

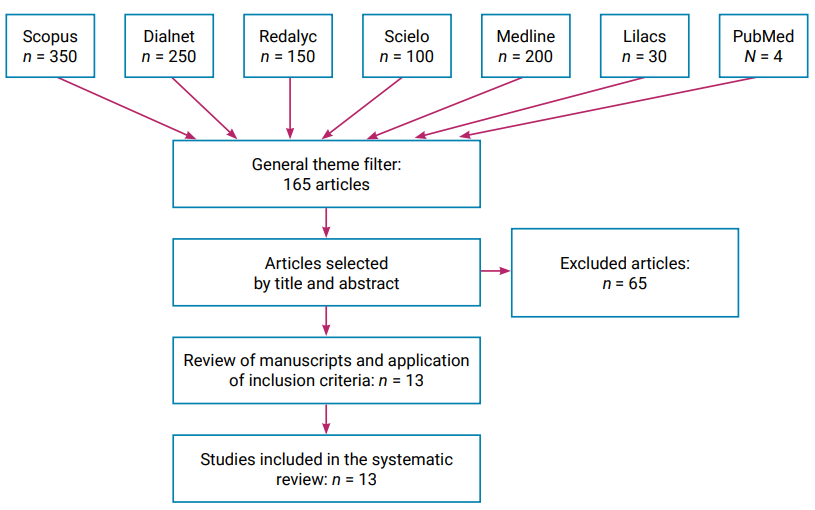

Fig. 1. Own elaboration based on PRISMA-COCHRANE model

Among the search terms were “neurotechnology,” “personal data,” “mental privacy,” “neuro-rights,” “neurotechnological interventions,” and “neurotechnological discrimination,” and they were used to find both English and Spanish sites. The systematic literature review was based on the methodology proposed by a renowned British scholar, a professor emerita of computer science at Keele University Barbara Kitchenham3, chosen for its flexibility and effectiveness in obtaining results for publication.

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion criteria

To assess the quality of evidence, only articles and reviews written in English or Spanish (see Table 1) involving institutions, researchers, and personnel related to neuro-rights were considered. Content analysis technique was applied to answer the research question. Duplicate articles, editorial comments, press releases, news, opinions, and clinical recommendations were excluded. Articles were filtered to select the most relevant ones, and full research papers related to neuro-rights in patients were reviewed.

2.2. Population and Sample

The population analyzed was based on the selected research articles that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria established in the design phase, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Research on neurorights and neurotechnologies

|

N |

Autor |

Theme |

Year |

|

1 |

E. Cáceres, J. Diez, E. García |

Neuroethics and neurorights |

2021 |

|

2 |

A. R. González |

“Neurorights”, evidences of neuroscience and guarantees |

2021 |

|

3 |

M. Ienca |

On Neurorights |

2021 |

|

4 |

M. Ienca, R. Andorno |

Approaches to new human rights in the era of neuroscience |

2021 |

|

5 |

S. Ruiz, V. Ramos, R. Concha, et al., C. Caneo |

Negative effcets of the Law 20.584 and the discussed Law |

2021 |

|

6 |

Y. V. Bastidas Cid |

Neurotechnology: the brain-computer interface and the protection of brain- or neurodata in the context of personal data processing in the European Union |

2022 |

|

7 |

C. López, N. Cáceres |

Neuroright as a new sphere of human rights protection |

2022 |

|

8 |

R. Orias |

Neurorights. New frontier in human rights |

2022 |

|

9 |

V. E. Rocha Martínez |

Neuroright as a new sphere of human rights protection |

2022 |

|

10 |

H. Fernández |

Neurorights, neurotechnologies and risk management in modernity. Historical analysis, dialectics and holistic approach |

2023 |

|

11 |

P. López-Silva, R. Madrid |

Protecting the mind: analysis of the concept of the mental in the Law on neurorights |

2023 |

|

12 |

J. I. Murillo |

On the possibility of mind-reading or the external control of behavior: Contribution of Aquinas to the Neurorights discussion |

2023 |

|

13 |

W. Arellano |

Neurorights and their regulation |

2024 |

-

Research results

Table 1 shows the number of selected primary studies evidencing the authors’ studies and research in the field of neuro-rights and neurotechnology. These studies reflect opinions or criteria regarding the inappropriate handling of patient information, lack of legal security guarantees, and susceptibility to being undervalued, which may potentially result in misuse behaviors and mishandling of information (Borbón et al., 2020).

3.1. Data collection and Analysis

To facilitate and summarize the contents of the selected articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a Systematic Literature Review was employed. This tool outlines an open and understandable procedure for gathering and choosing various articles and information sources.

Initially, the following search phrases were used in the aforementioned databases: “neuro-rights,” “personal data,” “mental privacy,” “neurotechnological discrimination,” and “access to neuroscientific data.” 1084 articles in all were acquired. 165 articles that satisfied the selection criteria were selected after the titles and abstracts were reviewed. Following a thorough reading of all the articles, 13 were chosen for the final review.

The literature study made it possible to identify the following rights and issues at the nexus of neuro-rights and personal data:

Challenges:

– Mental Privacy: People’s mental privacy may be threatened by the gathering and processing of neuroscientific data.

– Neurotechnological Discrimination: There’s a chance that people will be singled out for special treatment because of their unique neurobiological traits.

– Access to Neuroscientific Data: Maintaining the privacy of individuals is as important as advancing scientific research when it comes to access to neuroscientific data.

Rights:

– Right to Mental Privacy: People are entitled to decide how their neuroscientific data is gathered, used, and shared.

– Right to Neurotechnological Non-Discrimination: People are entitled to be treated equally regardless of their neurobiological traits.

– Right to Access Neuroscientific Data: People are entitled to view the neuroscientific data that pertains to them as well as the data that is used to inform judgments about them.

– Right to Mental Identity: The idea of the self in which a person chooses and maintains their personal identity.

– Right to Free Will: The ability to choose for oneself.

3.2. Discussion of the results

Table 2 outlines moral practices that should be taken into account when providing medical care in the area of neuro-rights in order to preserve and uphold patients’ liberties and rights.

Table 2 Main principles of rendering medical assistance in the sphere of neurorights

|

No |

Behaviors |

|

A |

Honesty |

|

B |

Free access |

|

C |

Equity |

|

D |

Justice |

|

E |

Professional secret |

|

F |

Information Privacy |

|

G |

Integrity |

|

H |

Transparency |

|

I |

Informed Consent |

|

J |

Responsibility |

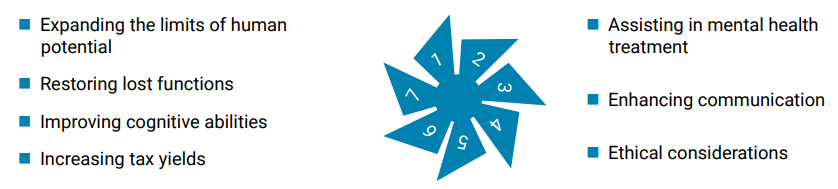

The company FasterCapital4 highlights the advancements of neurotechnologies in various sectors, such as education and healthcare, driving innovation and improving the quality of life for individuals with conditions like ALS, mental health disorders, and communication difficulties. However, it is important to delve into aspects related to privacy, consent, and equitable access to these technologies by service-providing companies. Figure 2 demonstrates the potential for enhancement in human capabilities, based on data provided by FasterCapital.

Fig. 2. Understanding the potential of neurotechnologies to improve human capabilities

The systematic review provides scientific evidence of the positive impact of neurotechnologies in treating diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, psychosis, dementia, and sensory and motor functions of the central nervous system, as well as in pain medicine. Neurotechnological interventions may represent an effective treatment option for individuals with mental disorders who do not respond to traditional treatments. However, further research is needed to confirm these results and assess the long-term safety and efficacy of such interventions (Andorno, 2023; Ruiz et al., 2021).

The results obtained from the Systematic Literature Review underscore the need to ethically address the challenges posed by neurotechnologies in the realm of regulations, as mentioned in each of the studies included in this research. There is a call for expanding the literature related to neurotechnologies to protect individual rights (Andorno, 2023; Arellano, 2024; Cid, 2022; Borbón et al., 2020; Cáceres et al., 2021; Fernández, 2023; Goering et al., 2021; Baselga-Garriga et al., 2022).

Additionally, several authors propose basic deontological principles that incorporate respect and assistance to others, thereby promoting ethics in the use of neurotechnologies. In this regard, the Organization of American States (OAS) develops an educational program centered on values that fosters the socialization of attitudes and norms to create new constructs that promote harmony among all involved parties.

Conclusions

In conclusion, existing regulatory frameworks must adapt to address the ethical and social challenges posed by emerging neurotechnologies. Ensuring the preservation of individual rights, privacy, and mental autonomy requires the establishment of policies and regulations.

Moreover, increased cooperation between organizations, scientists, and businesses is necessary for the responsible development and use of neurotechnologies. This entails encouraging openness, informed permission, and fairness in the use of these technologies.

Evidence of the potential advantages of neurotechnologies in treating a range of illnesses and mental health issues may be found in the systematic literature review. Nonetheless, more investigation is required to assess their long-term efficacy and safety.

The significance of enlightening the public about the moral and legal implications of neurotechnologies is also emphasized. In the area of applied neuroscience, this entails advancing deontological ideas that support the respect and defense of human rights.

In conclusion, as new neurotechnologies arise, regulatory frameworks must adapt to meet the ever-changing moral and societal issues they raise. To guarantee that these technologies be used morally and responsibly for the good of society, multidisciplinary cooperation and a proactive attitude are needed.

1 Universidad Santiago de Chile. (2021). Cambalache, 4. (In Spain). https://clck.ru/3Ct9Wi

2 UNESCO. (2021). Report of the International Bioethics Comittee of UNESCO (IBC) on ethical issues of neurotechnology. https://clck.ru/3Ct9sj

3 https://goo.su/PmZdwxj

4 Neurotech Startups and the Future of Human Enhancement. URL: https://clck.ru/3DvQTJ

References

1. Alharbi, H. (2023). Identifying thematics in a brain-computer interface research. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 4, 2793211. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/2793211

2. Andorno, R. (2023). Neurotecnologías Y Derechos Humanos En América Latina Y El Caribe: Desafíos Y Propuestas De Política Pública. University of Zurich; UNESCO. https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-237729

3. Arellano, W. (2024). Los Neuroderechos y su Regulación. Inteligencia Artificial, 27(73), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.4114/intartif.vol27iss73pp4-13

4. Barrios, L., Minguillón, J., Perales, F., Ron-angevin, R., Solé, J., & Mañanas, M. (2017). Estado del Arte en Neurotecnologías para la asistencia y la Rehabilitación en España: Tecnologías Auxiliares, Transferencia Tecnológica y Aplicación Clínica. Revista Iberoamericana de Automática e Informática Industrial RIAI, 14(4) 355–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riai.2017.06.004

5. Cid, Ya. V. B. (2022). Neurotecnología: Interfaz cerebro-computador y protección de datos cerebrales o neurodatos en el contexto del tratamiento de datos personales en la Unión Europea. Informática y Derecho, 11.

6. Baselga-Garriga, C., Rodriguez, P., & Yuste, R. (2022). Neuro Rights: A Human Rights Solution to Ethical Issues of Neurotechnologies. In P. López-Silva, & L. Valera (Eds.), Protecting the Mind. Ethics of Science and Technology Assessment (Vol. 49). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94032-4_13

7. Bastidas Cid, Y. V. (2022). Neurotecnología: Interfaz cerebro-computador y protección de datos cerebrales o neurodatos en el contexto del tratamiento de datos personales en la Unión Europea. Informática Y Derecho. Revista Iberoamericana De Derecho Informático (2.ª época), 11, 101–182.

8. Borbón, D., & Borbón, L. (2022). NeuroDerechos Humanos y Neuroabolicionismo Penal. Cuestiones Constitucionales, 1(46), 29–64. (In Spain). https://doi.org/10.22201/iij.24484881e.2022.46.17047

9. Borbón, D., Borbón, L., & Laverde, J. (2020). Análisis crítico de los NeuroDerechos Humanos al libre albedrío y al acceso equitativo a tecnologías de mejora. Ius Et Scientia, 6(2), 135–161. https://doi.org/10.12795/ietscientia.2020.i02.10

10. Bublitz J-C. (2013). My Mind is Mine!? Cognitive Liberty as a Legal Concept. In: Hildt E., & Franke A. (Eds.), Cognitive Enhancement. An Interdisciplinary Perspective (pp. 233–264). Dordrecht: Springer.

11. Cáceres, E., Diez, J., & García, E. (2021). Neuroética y NeuroDerechos. Revista del Posgrado en Derecho de la UNAM, 15, 37–86. https://doi.org/10.22201/ppd.26831783e.2021.15.179

12. Cáceres, E. & López, C. (2022). El neuroderecho como un nuevo ámbito de protección de los derechos humanos. Cuestiones Constitucionales, 1(46), 65–92. https://doi.org/10.22201/iij.24484881e.2022.46.17048

13. Clausen, J. E., Fetz, J., Donoghue, J., Ushiba, J., Spörhase, U., Chandler, J., Birbaumer, N., & Soekadar, S. R. (2017). Help, hope, and hype: Ethical dimensions of neuroprosthetics. Accountability, responsibility, privacy, and security are key. Science, 356(6345), 1338–1339. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aam7731

14. Cornejo-Plaza, M. I., Cippitani, R., & Pasquino, V. (2024). Chilean Supreme Court ruling on the protection of brain activity: neurorights, personal data protection, and neurodata. Frontiers in Psychology, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1330439

15. Filipova, I. A. (2022). Neurotechnologies in law and law enforcement: past, present and future. Law Enforcement Review, 6(2), 32–49. https://doi.org/10.52468/2542-1514.2022.6(2).32-49

16. Fernández, H. (2023). Neuroderechos, neurotecnologías y administración de riesgos en la modernidad, Análisis histórico, dialéctica Holismo. Tzhoen, 15(1), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.26495/tzh.v15i1.2457

17. Fukushi, T. (2024). East Asian perspective of responsible research and innovation in neurotechnology. IBRO Neuroscience Reports, 16, 582–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibneur.2024.04.009

18. Goering, S., Klein, E., Specker Sullivan, L. et al. (2021). Recommendations for Responsible Development and Application of Neurotechnologies. Neuroethics, 14, 365–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-021-09468-6

19. Gómez, R. M. (2021). Inteligencia artificial y neuroderechos. Retos y perspectivas. Cuestiones Constitucionales, 1(46), 93–119. https://doi.org/10.22201/iij.24484881e.2022.46.17049

20. González, A. R. (2021). “Neuroderechos”, prueba neurocientífica y garantía de independencia judicial. Derecho & Sociedad, 57, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18800/dys.202102.007

21. Hertz, N. (2022). Neurorights – Do we Need New Human Rights? A Reconsideration of the Right to Freedom of Thought. Neuroethics, 16, 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-022-09511-0

22. Hsu, J. (2024). Privacy concerns over brain monitors. The New Scientist, 262(3490), 10. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0262-4079(24)00850-9

23. Ienca, M. (2021). On Neurorights. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 15, 701258. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2021.701258

24. Ienca, M., & Andorno, R. (2021). Hacia nuevos derechos humanos en la era de la neurociencia y la neurotecnología. Análisis Filosófico, 41(1), 141–185. https://doi.org/10.36446/af.2021.386

25. López, C., & Cáceres, E. (2022). El neuroderecho como un nuevo ámbito de protección de los derechos humanos. Cuestiones Constitucionales, 46. https://doi.org/10.22201/iij.24484881e.2022.46.17048

26. López-Silva, P., & Madrid, R. (2022). Protecting the Mind: An Analysis of the Concept of the Mental in the Neurorights Law. RHV, 20, 101–117. http://dx.doi.org/10.22370/rhv2022iss20pp101-117

27. Makin, J. G., Moses, D. A., & Chang, E. F. (2020). Machine translation of cortical activity to text with an encoder decoder framework. Nature Neuroscince, 23, 575–582. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-020-0608-8

28. Moreu, C. E. (2022). La Reulación de los neuroderechos. Revista General de Legislación y Jurisprudencia, 1, 69–98. https://doi.org/10.30462/rglj-2022-01-04-840

29. Murillo, J. I. (2023). On the possibility of mind-reading or the external control of behavior: Contribution of Aquinas to the Neurorights discussion. Scientia et Fides, 11(2), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.12775/SetF.2023.017.

30. Orias, R. (2022). Los neuroderechos. Una nueva frontera para los derechos humanos. Agenda Internacional, XXIX(40), 211–227. https://doi.org/10.18800/agenda.202201.009

31. Parlatino. (2023). Ley modelo de Neuroderechos para América Latina y el Caribe. (In Spain).

32. Reguera, A. M., & Cayón, J. (2021). La Garantía de los Neuroderechos: A propósito de las iniciativas emprendidas para su reconocimiento. Derecho y salud, 31(1), 213–222.

33. Rocha Martínez, V. E. (2022). Nuevos derechos del ser humano. Cuestiones Constitucionales. Revista Mexicana De Derecho Constitucional, 1(46), 251–277. https://doi.org/10.22201/iij.24484881e.2022.46.17055

34. Ruiz, S., Ramos, P., & et al, Caneo, C. (2021). Efectos negativos en la investigación y el quehacer médico en Chile de la Ley 20.584 y la Ley de Neuroderechos en discusión: la urgente necesidad de aprender de nuestros errores. Revista médica de Chile, 149(3). https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/s0034-98872021000300439

35. Sententia, W. (2004). Neuroethical Considerations: cognitive liberty and converging technologies for improving human cognition. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1013(1), 221–228. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1305.014

About the Author

Y. CornejoEcuador

Yan Cornejo – Magister, CEO of Academia Cibers, Private Consultant Data Privacy, Independent Researcher

La Fae mz 32 villa 18, Guayaquil

WoS Researcher ID: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/author/record/KWU-8753-2024

Google Scholar ID: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=clFiXCsAAAAJ

Competing Interests:

The author declares no conflict of interest.

- ethical principles to protect individual rights and promote the responsible use of neurotechnology;

- key neuro rights - mental privacy, mental integrity, personal identity, and cognitive freedom;

- the potential of neurotechnology to improve human abilities;

- research map and trends related to neurorights and neurotechnologies of the future.

Review

For citations:

Cornejo Y. Neurorights, Neurotechnologies and Personal Data: Review of the Challenges of Mental Autonomy. Journal of Digital Technologies and Law. 2024;2(3):711-728. https://doi.org/10.21202/jdtl.2024.36. EDN: sperfj