Scroll to:

Digital History of Law: Principles of Methodology

https://doi.org/10.21202/jdtl.2024.2

EDN: cfnahc

Abstract

Objective: to theoretically substantiate the basic principles of methodology of a new interdisciplinary area of socio-humanities – the digital history of law; to demonstrate the heuristic potential of digital technologies in legal historical sciences.

Methods: the study is based on systemic, formal-logical, and comparative general scientific methods.

Results: it is concluded that the methodology of the digital history of law is based, first of all, on the source-centric approach, which considers a source as a macro-object of humanitarian and social sciences, through which information exchange takes place (O.M. Medushevskaya’s concept of cognitive history). Secondly, it is based on the combination of traditional methods of legal history with digital techniques and technologies and methods based on them – within a research program of historical-legal (historical-juridical) source studies. The article attempts to summarize the existing digital technologies and techniques, as well as methods based on them, as applied to legal historical sciences; their heuristic potential is shown in case studies.

Scientific novelty: for the first time in the Russian legal history science, the author substantiates the methodology of the digital history of law as an interdisciplinary field that studies the past of state and law using digital information and communication technologies and tools.

Practical significance: under the shifts in socio-humanities (digital, linguistic, visual ones, etc.), which have become relevant in recent years, and the development of the digital type of social communication, methodological approaches to obtaining new knowledge are changing, new interdisciplinary branches of scientific knowledge are emerging, as well as new requirements for the qualification of researchers. The ongoing changes affect legal historical sciences: digital history of law is formed as an interdisciplinary area within digital humanities, at the confluence of history, legal science, and information science. The understanding and application of digital technologies and the scientific cognition methods based on them in legal historical research open up new opportunities for legal historians in determining the directions of their scientific research and obtaining new scientific results. This ultimately expands our understanding of historical and legal facts, phenomena and processes.

Keywords

For citations:

Lonskaya S.V. Digital History of Law: Principles of Methodology. Journal of Digital Technologies and Law. 2024;2(1):14–33. https://doi.org/10.21202/jdtl.2024.2. EDN: cfnahc

Introduction

Understanding science as a sphere of human activity, where new knowledge is produced and exchanged, allows considering this process from the information perspective: information per se is data, knowledge about the world1. The connection between the ways of storing, processing and transmitting information, on the one hand, and the forms of human perception and thinking, on the other hand, that has long been established in science (MacLuhan, 2018) gives grounds to assert that the types of information transmission in society also influence scientific knowledge in terms of its methodology. Therefore, we understand the digital turn in science as a state of change in methodological approaches to obtaining new knowledge as a result of the emergence of electronic (digital) type of social communication.

In recent decades, the disciplinary structure of science in the world has been enriched by a complex of digital sciences. Digital humanities, as an example of such a complex of academic disciplines based on digital technologies, has already gained sufficient influence, formed a wide community, and is evolving in terms of theoretical issues development, despite some skeptical researchers (Goebel, 2021).

The digital history of law is gradually maturing within the framework of digital humanities. While remaining within its subject (the study of the past of law and state), digital history of law acquires new knowledge using digital information and communication technologies and tools, which in the disciplinary structure of science brings it into the circle of interdisciplinarity in terms of methodology. Formulating the principles of this methodology for legal historians is an emerging important scientific problem, the solution of which has begun in recent years (Birr, 2016; Robertson, 2016; Tanenhaus & Nystrom, 2016b; Küsters et al., 2019; Volkaert, 2021). Below we define the main levels of methodological knowledge and their content in relation to the digital history law, summarize and demonstrate the heuristic potential of modern digital technologies and methods based on them in the application to legal historical sciences.

1. Model of the methodological knowledge structure applied to a particular scientific discipline

The methodology of the digital history of law can be justified as a model based on general ideas about the structure of methodology (methodological knowledge). According to a philosopher E. G. Yudin (Yudin, 1978), four levels can be distinguished:

- philosophical methodology: general principles of cognition, prerequisites and guidelines of cognitive activity, categorical structure of science;

- general scientific methodology: concepts affecting a group of fundamental scientific disciplines, relatively indifferent to a specific subject area;

- specific-scientific methodology: a set of methods, research principles and procedures applied in a particular scientific discipline, with appropriate subject interpretation and development;

- methodology and technique of scientific research: a set of procedures that ensure the acquisition and primary processing of empirical material, provided the requirements of reliability and uniformity are observed.

Approximately the same four-level structure is proposed by a legal scholar N. N. Tarasov: philosophical means, general scientific means, special legal means, research methods and techniques (Tarasov, 2001).

D. A. Kerimov also distinguishes four levels: dialectical and world outlook level, general scientific (interdisciplinary), specific scientific, and transitional from cognitive-theoretical to practical-transformative activity (Kerimov, 2001). At the same time, the scholar does not include research methods and techniques in some of the levels, as they “do not reflect objective regularities of cognition and therefore lack methodological significance” (Kerimov, 2001).

S. V. Kodan, substantiating the methodology of historical and legal source study as a separate academic discipline, proceeds from five levels of methodological means: methodological principles, methodological approaches, specific scientific methods, research methodology, and research techniques (Kodan, 2018). He also distinguishes two generalized levels of methodological knowledge: specific-academic methodology (principles, approaches, methods) and procedural-academic methodology, which includes methods, techniques (resources and means) and technologies (methods of using techniques and ways to organize activities). The first level contains general requirements and determines a set of cognitive tools, while the lower level is operational, acting as a set of methodological tools-operations (Kodan, 2022a).

This, however, does not mean that the two higher levels (philosophical and general scientific) fall out of the general picture. They remain, because they are “relatively indifferent”, according to E. G. Yudin (Yudin, 1978), to a specific subject area, but, taken as a whole, they set the research paradigm or research program (Kotenko, 2006; Kun, 2003; Lakatos, 1995). As for the inclusion of methods, techniques and technologies into the scientific cognition methodology, it is justified precisely because of their isolation as an instrumental-operational component (level) of scientific research methodology, especially in the context of information (computer, digital) technologies application. We believe that the digital research methodology originates from the techniques and technologies formed since the middle of the last century, when the computer era began. Information and communication techniques and technologies, in turn, have formed new techniques and methods or brought significant transformations to the already existing ones.

In fact, the philosophical, general scientific and specific scientific levels of methodology have a similar structure and can be united into a single macro-level, which we may call paradigmatic (normative), since research principles, approaches and methods (general scientific paradigm, general scientific and specific scientific research program) are defined at this level. As we have already noted, means, techniques and technologies taken together form not just procedural, but instrumental level of methodology. It is this structure of methodological knowledge that we will further stem from.

2. Philosophical and general scientific levels of methodology of the digital history of law

E. G. Yudin defines a methodological approach as “a principal methodological orientation of research, a point of view from which the object of study is viewed (a way of defining the object), a concept or principle guiding the general strategy of research” (Yudin, 1978). Let us note another important remark of the philosopher: scientific research is built, as a rule, on a set of approaches, provided that they do not mutually exclude each other and are adequate to certain types of research tasks (Yudin, 1978).

The philosophical level determines a researcher’s most general worldview positions – both ontological and epistemological. In this article we will not analyze and describe in detail the philosophical and worldview foundations of scientific research, but will just assert the fact that traditionally, in the scientific-methodological and educational literature of this level, the opposing metaphysical and dialectical approaches are distinguished2, although modern post-classical science is moving away from this dichotomy (Chestnov, 2012).

Descending to the level of general scientific concepts affecting a group of scientific disciplines and serving as a transitional link from general philosophical matter to specific disciplines, we obviously get into the circle of concepts within the framework of digital socio-humanities (digital humanities) and general research tasks solved within the digital turn in humanitarian knowledge. The academic status of digital humanities as a very new field is still not completely defined. The metaphor of a certain methodological or technological “umbrella” over the humanities, we believe, cannot be regarded as a scientific category. However, the main lines of research in the digital humanities, and thus the tasks, are already clear, and there is a key aspect that unites them: digital research is about working with data using digital tools3.

But where do the data come from? The answer is obvious: from a variety of sources. Searching, processing and interpreting sources, obtaining new information from them, further work with this information recoded into data, and other scientific work – these are the basic research procedures carried out with digital methods, techniques and technologies. Hence, we believe that the concept of cognitive history by O. M. Medushevskaya (<Medushevskaya, 2008), based on the phenomenological paradigm, can be accepted as the leading general scientific methodological concept of digital humanities. It considers a source as an empirical reality, a macro-object of all disciplines studying man and society, through which information exchange in society takes place. In our opinion, this “source-centered” methodological approach and, within its framework, the general scientific source method set the paradigm of digital socio-humanitarian research. S. V. Kodan calls it a source-study paradigm (Kodan, 2022b).

The source-centered approach, defined as the main research reference point, can be combined with other well-known general scientific principles and approaches: objectivity, historicism, systemic, comparative, structural-functional, anthropological, activity-based, network, institutional approach, etc. The concrete combination of general scientific principles, approaches and methods (theoretical and empirical) will depend on the subject, problems and objectives of a particular study, formulated at the next level of methodological knowledge, as well as on the data at the researcher’s disposal.

3. Specific-scientific and instrumental-operational levels of the methodology of the digital history of law

3.1. Methodology of digital history of law in the aspect of research subject and sources

History of law is an inherently interdisciplinary area at the intersection of history and jurisprudence. By definition, digital history of law expands its boundaries even further. We understand it as an interdisciplinary field within digital humanities, at the intersection of history, jurisprudence, and computer science. At the same time, digital history of law remains within its traditional subject – the study of legal facts, phenomena and processes of the past, the synthesis between historical analysis of legal situations and legal analysis of historical situations. The connection with digital humanities and informatics at the digital turn enriches the history of law not in terms of subject matter, but in terms of methodology.

At the level of the specific scientific methodology of legal history research, the general scientific source-centered approach and the source study method (source study paradigm) are mainly transferred to the methodology (research program) of the history of law (historical-juridical) source studies (Kodan, 2018, 2022a, 2022b). A historian of law deals with historical-legal sources, through which the history of state-legal phenomena and processes is cognized. Because of this, a set of traditional principles, approaches and methods, inherent in historical-legal studies, is preserved. Historical-genetic, comparative-historical, comparative-legal, formal-legal methods, the method of interpretation of law and others remain in the arsenal of a digital historian of law, especially at the stage of primary processing and interpretation of sources. However, the problem of sources is approached differently, as at this methodological level a researcher works not just with sources, but also with data.

Humanitarian data are various. The authors of the manual Introduction to digital humanities research4 give the following examples: text files; data collected through parsing and APIs from the Internet; digital images; geospatial data; audio files; metadata. The main property of the data that can be handled using digital technologies is their formalization. Some data must be pre-transformed to acquire a formalized machine-readable form. For example, text files are marked up (this is called data annotation), accumulated into text corpora, and then they are suitable for processing and retrieving new information using, for example, mathematical linguistics methods and computer tools.

Can humanitarian data be a legal-historical source? It seems that the development of modern historical and legal source studies gives a positive answer to this question. Data are extracted from sources; sources are transformed into data. It is probably more important to consider the problem from a technological point of view: how to carry out procedures of coding “texts” (historical and legal sources in the broadest sense) into “data”, how to apply computer tools in research and how to analyze the data. This, undoubtedly, requires a sufficient level of a researcher’s digital qualification.

3.2. Terminology and structure of the instrumental-operational level of the methodology of the digital history of law

Above we did not give separate definitions for methodological principles and research methods, believing that, despite the variety of existing definitions, the meaning of these concepts is clear to the reader. The definition of a methodological approach is given according to E. G. Yudin (Yudin, 1978), as it has passed the test of time and is not outdated. One may argue, for example, what is more primary – principles or approaches, but here we do not seek to resolve this dispute. We hope that the author’s position is clear: we prioritize principles as initial ideas and provisions. The detailed development of methodological principles of digital history of law is a separate big question, and we put it out of the scope of this article. It seems that, in addition to the traditional principles of the history of law, we can first of all talk about the principles related to information technologies and data: for example, the principles of data quality (completeness, reliability, comparability), principles of interpretation, visualization, etc.

As we have already shown, when describing the content of the instrumental-operational level of methodological knowledge authors mainly use the categories of “methodology” and “technique”. S. V. Kodan adds technology to this (Kodan, 2022a). In a very simplified form, we would reduce it all to methods and means, but the requirements of sufficiency and completeness make it necessary to put everything in its place, at least in the context of this paper.

In contrast to a method, methodology is the practical implementation of a method. While a method defines the way to achieve a scientific result, a methodology is a sequence, an algorithm of actions and procedures aimed at achieving a scientific result. For example, if you apply the method of correlation analysis, the methodology will include data collection, selection of the type and measure of correlation of signs, and numerical calculations per se.

Assumingly, fulfillment of the specific elements of methodology will involve using cognition tools, with the help of which the research will be carried out. These may not necessarily be material things (computers, for example). A cognition tool is language, with which we name phenomena and introduce unambiguous concepts and definitions. A tool is logic, which helps us to make judgments and inferences. Tools are computer programs, measuring scales, etc.

In our opinion, one may unite tools and resources under the notion of “means”, especially since the Encyclopedia of Philosophy defines technique through the generic notion of “means”, mentioning also “tools”, and makes a reservation that technique also includes knowledge and skills with the help of which people use these means5. However, in methodological literature the term “technique” is more often used, and we will adhere to it.

A tool can be operated using various techniques, i.e. specific ways of application. For example, you have chosen a chart tool to visualize and analyze data. Selecting a chart type, captioning data on the chart and other operations are part of the techniques for using this tool. To build a chart, you choose another digital tool – a special computer program (editor), the techniques of working with which you also need to master. The techniques are no longer an instrumental, but an operational component of the research, associated with the concept of technology.

The meaning of the “technology” concept and its correlation with technique is very ambiguous. A philosopher E. V. Ushakov notes this fact and uses the “technique” concept in the narrow sense – as a set of technical objects, artifacts specially created and used by man (tools, instruments, devices, machines, etc.)6. As for technology, E. V. Ushakov counts no less than five etymological meanings of this term, including – in compliance with the approach of a philosopher C. Mitcham, as an object, process, knowledge, type of activity, and willful aspiration7. S. V. Kodan considers technology in a specific sense – as a research and methodological tool, a system of cognitive means (Kodan, 2022a). In this he echoes R. G. Valiev, who defines legal technology as “an organizational and functional mechanism of implementation of the instrumental arsenal of legal technique” (Valiev, 2016).

It should be noted that the concepts of legal technique and legal technology have been developed in detail in the legal doctrine. The history of these doctrinal concepts development is thoroughly described, for instance, by M. V. Zaloilo8. For example, S. S. Alekseev interpreted legal technique as a set of means (technique proper) and methods (technologies)9. V. M. Baranov10, N. A. Vlasenko (Vlasenko et al., 2013), and A. N. Mironov (Mironov, 2008) adhere to the activity approach in the definition of legal technology.

Returning to the philosophical definition of technology, let us point out its essential principles: rationality, purposefulness, reproducibility, efficiency, and effectiveness. According to the definition of E. V. Ushakov, “the presence of technology in the modern sense for a specific activity implies, as a rule, the existence of a structured way of action supported by effective material and technical means”11.

Thus, the instrumental-operational level of the methodology of the digital history of law includes:

- methods: description of the sequence, algorithm of actions and procedures aimed at achieving a scientific result;

- techniques: tools (means) and resources with the help of which the methods are implemented;

- technologies: methods of using techniques and ways of organizing research activities.

3.3. Methodology of the digital history of law in action: how does it work?

As we have already pointed out, the new scientific issues and tasks formulated by a digital historian of law entail the expansion of methodological foundations, as well as the use, along with traditional ones, of new research methods and techniques related to the application of digital technologies. The said scientific issues and tasks may refer to all three components (directions) of the digital turn (Garskova, 2019): the resource (creation of databases, digitization of sources), the analytical (obtaining new knowledge), and the applied (application of digital platforms). An approximate algorithm of a researcher’s activity in the digital environment will include steps for collecting and primary processing of information (creating databases, translating “text” into “data”, its structuring, visualization, etc.) and directly obtaining new information, which should be analyzed, interpreted, stored and decoded again into the usual “text” of a scientific article, report, etc.

For example, this is how a Belgian researcher F. Volkaert describes the concrete-scientific level of his research methodology12. Within his study he set three problems (research questions): to define the key provisions of European trade agreements; to describe the content of the international trade law doctrine; to describe diplomatic practice. If we use traditional methods to solve these problems, we can focus on textual analysis (interpretation of law) and historical-genetic method. But if we also apply digital methods that complement (not replace!) the traditional ones, then a researcher may choose network analysis methods (discourse network analysis, bibliometric analysis) and the method of mathematical linguistics (natural language processing). Certainly, the use of the mentioned digital methods was based on the corresponding methods, techniques and technologies that constitute the instrumental-operational level of the research methodology: creating a database of contracts, visualizing citations, qualitative content analysis, use of the R programming language, etc.

Let us try to summarize what means of all this arsenal can be applied by digital legal historians.

The promising and already tested (Hitchcock & Turkel, 2016; Romney, 2016; Tanenhaus & Nystrom, 2016a, 2016b; Ward & Williams, 2016; Küsters et al., 2019; deJong & vanDijck, 2022) methods of the digital history of law include:

- quantitative (statistical) methods;

- methods of network analysis;

- methods of corpus (mathematical) linguistics;

- methods of computer modeling.

It is easy to notice that almost all these methods originate in the mathematical processing of sources. Quantitative history, thanks to the scientific school of I. D. Kovalchenko, was actively developed first in the USSR and then in Russia, and digital historical science began its formation on this basis. Calculations and their visualization became much easier with the advent of computers.

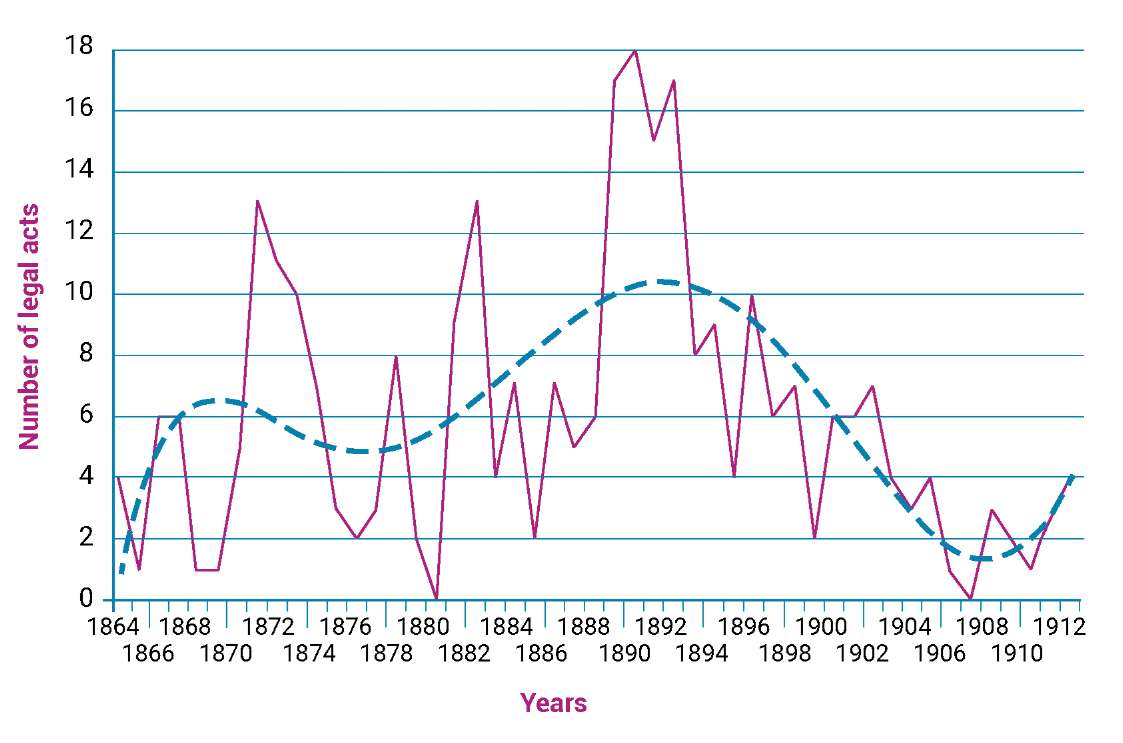

Quantitative research in the history of law using content analysis, correlation and regression analysis and other methods is quite appropriate, especially since mass sources (statistics, office records, etc.) are the subject of scientific interests of historians of law. For example, one of the quantitative methods applied by the author of this article in the doctoral dissertation was the statistical method of analyzing dynamic series13. Let us describe in detail the course of the research with methodological categories, starting for the sake of brevity from the specific-scientific level of methodological knowledge.

The hypothesis (research question, task) is that the historical periodization of the justice of the peace requires clarification of its second period chronological framework (“revision of the Judicial Statutes of 1864”). Different authors have tied it to different time points, which fit into the period from the early 1870s to the late 1880s. The main criterion for periodization is the law-making dynamics as an external factor of impact on the system. If the adoption of a legal act is considered as a variable that changes annually, then for this type of data the method of analyzing time dynamic series can reveal the desired patterns. Thus, the question is posed, the method is chosen. Let us move to the instrumental-operational level.

Based on the historical and legal source – the Complete Collection of Laws of the Russian Empire (and chronological and subject indexes to it) – we get the material for processing: the number of adopted legal acts by years (from 1864 to 1912), regulating the justice of the peace. Then we model a time dynamic series: we choose the type of series (simple, interval), fill in a table of data, draw a graph (in Microsoft Excel), calculate a trend line (since the data are unstable, a polynomial type of line is chosen). This is a methodology, technique and technology: an algorithm of actions, a set of resources (text of the Complete Collection) and means (computer, software, graph), methods of working with resources and means (construction of a table, graph, trend line).

The obtained results are interpreted. On the graph (Fig. 1) we see several maximums of law-making activity, and the trend line (dotted line) shows that from the late 1870s the dynamics is gaining growth, reaching a maximum around 1890. Thus, we quantitatively confirmed the analytically established chronological framework of the second period of the history of the justice of the peace in Russia, when law-making activity was the most intensive. Traditional logical, historical-comparative, formal-legal, and periodization method are supplemented by quantitative methods and digital technologies.

Fig. 1. Dynamics of legal acts adopted in the Russian Empire in 1864–1912,

related to the justice of the peace

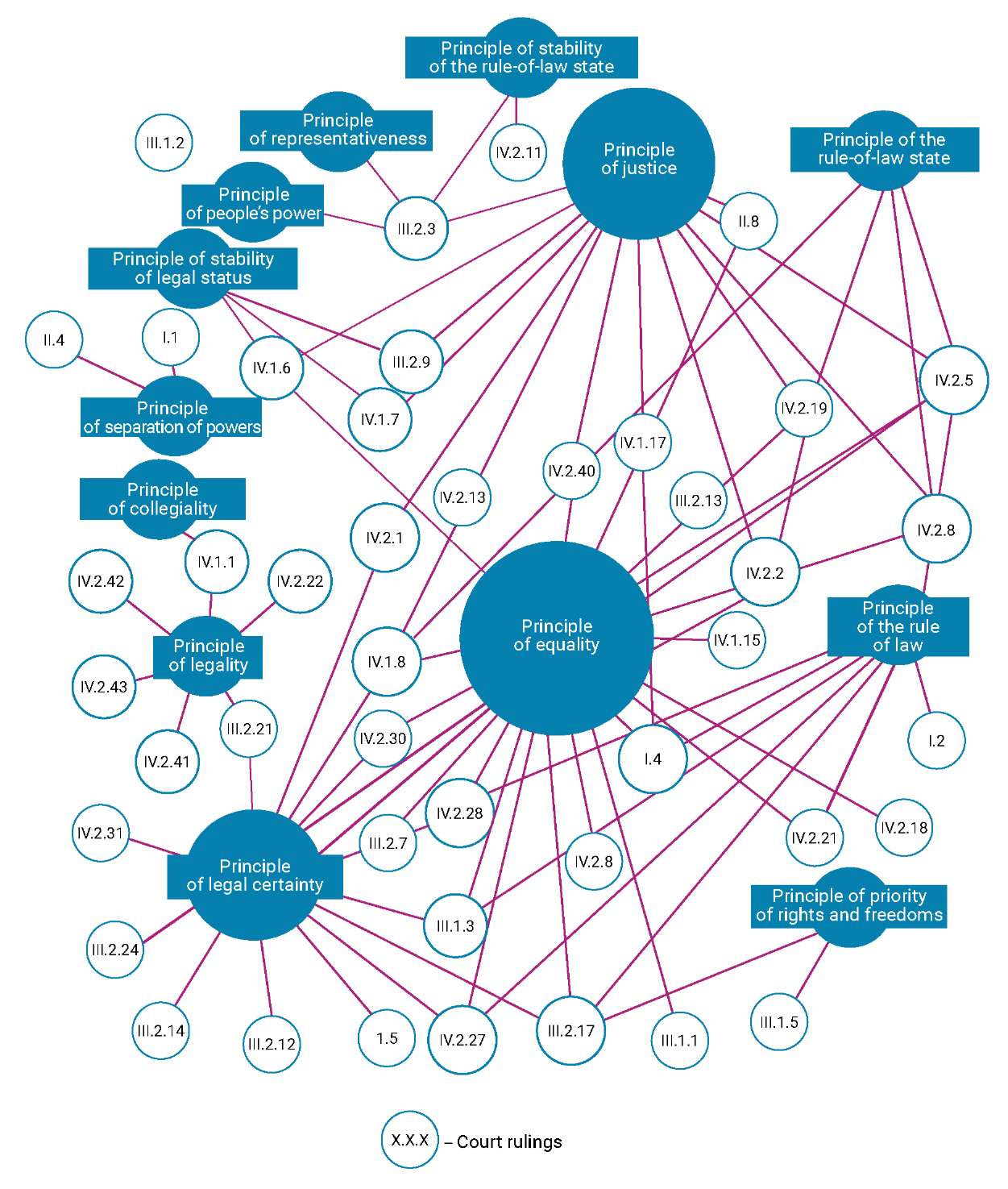

The above mentioned research by F. Volkeart showed an example of network analysis and computer linguistics methods. Below we present the result of our own research – network analysis of legal positions of the Kaliningrad oblast Charter Court, which was in force from 2003 to 2021.

The network nodes are court rulings (marked with indices) and legal principles mentioned in these rulings. Figure 2 shows that in its legal reasoning the court most often relied on the principles of equality, legal certainty and justice (these nodes are showed as the largest in size). Many rulings contain references to several legal principles at once. The graph was compiled by the author of the article using Gerhi software for network analysis and visualization and the database of systematized rulings and legal positions of the Charter Court of Kaliningrad oblast, prepared by a team of researchers of I. Kant Baltic Federal University. Most of the legal positions were published in 2020 (Lonskaya et al., 2020); the electronic database of rulings has been recently finalized.

Spatial and 3D modeling (using geographic information systems, mapping technology, etc.) helps to model the spatial dynamics of historical and legal phenomena and processes, their localization in time and space (chronotope), where legal communication takes place. Here we can mention several interesting research projects demonstrating how the method of computer modeling can be used in legal history: a 3D model of the Old Bailey’s Old Court14, a map of crimes in medieval London15, similar cases based on Russian statistics16, an interactive map of Scottish witch trials17.

Fig. 2. Legal principles in the argumentation of legal positions

of the Charter Court of the Kaliningrad oblast (2003–2021)

One may also note another area of application of the efforts of digital legal historians – the resource direction of the digital turn (digitization of sources, creation of databases). This is important not only for the preservation of existing sources and, in general, for facilitating their accessibility, but also for creating a body of data for researchers to work with. This is not simply a matter of converting printed publications into electronic file format (although this is necessary), but of creating corpora of legal texts, digital collections, libraries, search engines, etc. We would like to draw attention to a number of important achievements in this area.

First, it is worth mentioning the Complete Collection of Laws of the Russian Empire in digital form, prepared by the National Electronic Library, which is surely well known to legal historians18. We hope the project will be developed and the texts of the great monument of Russian law will become suitable for machine processing. Secondly, the corpus of legal texts RusLawOD (Institute for Problems of Law Enforcement, EUSPb)19. This project refers to the field of corpus linguistics. It covers the recent history of Russia, but someday digital legal historians will be able to work with the earlier legislation in this format. Thirdly, the Formulae-Litterae-Chartae project of the Academy of Sciences in Hamburg and the University of Hamburg – a study of medieval formulas in legal documents and collections, their digitization and database replenishment20. Perhaps such a bank of legal formulas from monuments of Russian law will eventually appear in our country. These are not the only examples of work in the resource area; more and more such projects are appearing, and the field of activity is vast. We have just drawn the readers’ attention to this issue of digital research in the history of law (especially the external history of law).

Digital tools – a key part of methodological technique – are developing faster than scholars acquire new knowledge. These are not only hardware – computers and peripherals – but also, and to a greater extent, software: from elementary applications included in office packages to entire intelligent systems. The market and offers in this area should be constantly monitored, because some tools come and go, while others are constantly being improved in new versions. It is necessary to understand the capabilities of these tools, their suitability for solving scientific problems, to be able to choose (and maybe to create) relevant tools for a particular scientific research and to be able to work with them. Again, this places additional demands on digital legal historians: one must have not only high qualifications as a researcher, but also the appropriate digital competence.

The heuristic potential of digital methods and technologies lies in the fact that they open up new possibilities for extracting information from sources and, when combined with traditional research methods, create a cumulative effect, expanding the boundaries of our understanding of the past of the state and law. When discussing the scope of “substitution” of human intellectual scientific creativity by digital technologies (and with the development of artificial intelligence, concerns of such “substitution” being uncontrolled and excessive are expressed more and more often), it is worth noting: one should not attribute subjectivity to artificial intelligence and similar entities. They are only tools, technologies. Undoubtedly, at the stages of searching, selecting, and processing of sources, they are indispensable helpers. But in the interpretation of new information, its axiologization, the subject is a human being – a scholar, a researcher engaged in creative scientific activity.

Conclusions

We have tried to construct, in the most general terms, the methodology of digital history of law, relying on the traditional structure of methodological knowledge developed in the Russian philosophy and legal studies. The paradigmatic (normative) macro-level of methodology, including philosophical, general scientific and specific-scientific levels, sets the principles, approaches and methods of research. Methods, techniques and technologies constitute the instrumental-operational level of methodology.

Based on the concept that a source is a macroobject of socio-humanitarian research (O. M. Medushevskaya’s concept of cognitive history), we have come to the conclusion that the digital history of law methodologically relies on the general scientific paradigm (“source-centered” approach and source-centered method). At the specific-scientific and instrumental-operational levels of methodology, digital history of law combines traditional approaches and methods of legal history with digital techniques and technologies, as well as methods based on them within the framework of the research program of historical-legal (historical-juridical) source studies. The direct combination of traditional and digital approaches depends on the subject matter, problems, and objectives of a particular research.

Thus, for the digital legal historian working at the intersection of history, law and computer science, it is not the subject of research that changes, but the methodology, which is centered on the understanding of historical and legal sources as carriers of information, data, from which the new scientific knowledge is extracted using digital tools and technologies. The completeness and objectivity of new scientific results can be achieved only by using a complex of traditional and digital cognitive tools. To obtain such results, we need a researcher who, in addition to the qualifications of a historian of law, has the necessary knowledge and skills to work in the digital world.

1. ISO/IEC 10746-2: 2009. Information technology – Open distributed processing – Reference model: Foundations – Part 2. https://clck.ru/37zw3i

2. Nemytina, M. V., Mikheeva, Ts. Ts., Lapo, P. V., & Gulyaeva, E. E. (2022). History and Methodology of Legal Science: tutorial for Master students (2nd ed.). Moscow: RUDN.

3. Puchkovskaya, A. A., Zimina, L. V., & Volkov, D. A. (2021). Introduction to digital humanitarian research: teaching and methodological manual. St. Petersburg: ITMO University. https://clck.ru/37zwUL

4. Puchkovskaya, A. A., Zimina, L. V., & Volkov, D. A. (2021). Introduction to digital humanitarian research: teaching and methodological manual. St. Petersburg: ITMO University. https://clck.ru/37zwUL

5. Rozin, V. M. (2010). Technique. New philosophical encyclopedia. In 4 vol. Vol. IV. Moscow: Mysl.

6. Ushakov, E. V. (2023). Philosophy of technique and technology: tutorial for universities. Moscow: Yurait.

7. Ibid.

8. Zaloilo, M. V. (2022). Modern legal technologies in law-making: scientific and practical manual. Moscow: IZiSP: NORMA: Infra-M. https://clck.ru/37zz7W

9. Alekseev, S. S. (1982). General theory of law: course of lectures (In 2 vol. Vol. 2). Moscow: Yuridicheskaya Literatura.

10. Baranov, V. M. (2000). Foreword. In: Issues of juridical technique. Nizhny Novgorod: Nizhniy Novgorod Academy of the Ministry of Domestic Affairs of the Russian Federation.

11. Ushakov, E. V. (2023). Philosophy of technique and technology: tutorial for universities. Moscow: Yurait.

12. Volkaert, F. (2021). Embedding free trade (1860–1865): visualising networks and arguments through discourse network analysis. Digital Methods and Resources in Legal History, Abstracts. Frankfurt. https://clck.ru/37zz5a

13. Lonskaya, S. V. (2016). Institute of the justice of the peace in Russia: historical and theoretical legal study: Dr. Sci. (Law) thesis. St. Petersburg. https://elibrary.ru/zhbfht

14. Voices in the Courtroom. Digital panopticon.https://clck.ru/3829gF

15. Eisner, M. (2018). Interactive London Medieval Murder Map. University of Cambridge: Institute of Criminology. https://goo.su/ijzUEg

16. Mapping crime and the growth of medieval towns: why historians need GIS. Sistemniy Blok. https://clck.ru/37zxjr

17. Interactive Witchcraft Map. https://goo.su/3VAO1zF

18. Complete Collection of Laws of the Russian Empire. RNB electronic library. https://clck.ru/37zyAE

19. Corpus of legal texts RusLawOD. GitHub. https://clck.ru/37zyCJ

20. Formulae – Litterae – Chartae. https://clck.ru/37zyDS

References

1. Birr, C. (2016). Die geisteswissenschaftliche Perspektive: Welche Forschungsergebnisse lassen Digital Humanities erwarten? Rechtsgeschichte – Legal History, 24, 330–334.https://doi.org/10.12946/rg24/330-334

2. Chestnov, I. L. (2012). Postclassical Theory of Law: monograph. Saint Petersburg: Alef-Press. https://elibrary.ru/qssdiv

3. de Jong, H., & van Dijck, G. (2022). Network analysis in legal history: an example from the Court of Friesland: Remarks on the benefits. Tijdschrift voor Rechtsgeschiedenis / Revue d’histoire du droit / The Legal History Review, 90(1–2), 250–262. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718190-20220004

4. Garskova, I. M. (2019). The “Digital Turn” in Historical Research: Long-term Trends. Historical informatics, 3, 57–75. https://doi.org/10.7256/2585-7797.2019.3.31251

5. Goebel, M. (2021). Ghostly Helpmate: Digitization and Global History. Geschichte Und Gesellschaft, 47(1), 35–57. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.13109/gege.2021.47.1.35

6. Hitchcock, T., &Turkel, W. J. (2016). The Old Bailey Proceedings, 1674–1913: Text Mining for Evidence of Court Behavior. Law and History Review, 34(4), 929–955. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0738248016000304

7. Kerimov, D. A. (2001). Methodology of law (subject, functions, issues of the philosophy of law): monograph (2nd ed.). Moscow: Avanta+.

8. Kodan, S. V. (2018). Methodology of historical-legal source studies: goal orientations, functional focus, level of organization of cognitive resources. Genesis: Historical research, 12, 67–80. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.25136/2409-868x.2018.12.28474

9. Kodan, S. V. (2022a). Research activity in jurisprudence: methodological problems of technologization and technologies. In: Juridical activity: content, technologies, principles, ideals: monograph. Moscow: Prospekt. (In Russ.).

10. Kodan, S. V. (2022b). Source study paradigm in modern jurisprudence: from the study of sources and forms of law to a scientific discipline. Legal Science and Practice: Journal of Nizhny Novgorod Academy of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia, 4(60), 12–21. (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.36511/2078-5356-2022-4-12-21

11. Kotenko, V. P. (2006). Paradigm as a methodology of scientific activity. Bibliosphere, 3, 21–25. (In Russ.).

12. Kun, T. (2003). Structure of scientific revolutions. Moscow: Progress. (In Russ.).

13. Küsters, A., Volkind, L., & Wagner, A. (2019). Digital Humanities and the State of Legal History. A Text Mining Perspectiv. Rechtsgeschichte – Legal History, 27, 244–259. http://dx.doi.org/10.12946/rg27/244-259

14. Lakatos, I. (1995). Falsification and methodology of scientific-research programs. Moscow: Medium. (In Russ.).

15. Lonskaya, S. V., Gerasimova, E. V., Landau, I. L., & Kuznetsov, A. V. (2020). Legal position of the Charter Court of Kaliningrad oblast. 2003–2018: scientific-practical edition. Moscow: Prospekt. (In Russ.).

16. MacLuhan, M. (2018). The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man. Moscow: Akademicheskii proekt. (In Russ.).

17. Medushevskaya, O. M. (2008). Theory and methodology of cognitive history: monograph. Moscow: Russian State University for the Humanities. (In Russ.).

18. Mironov, A. N. (2008). Juridical technology. Juridical Techniques, 2, 63–66. (In Russ.).

19. Robertson, S. (2016). Searching for Anglo-American Digital Legal History. Law and History Review, 34(4), 1047–1069. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0738248016000389

20. Romney, C. W. (2016). Using Vector Space Models to Understand the Circulation of Habeas Corpus in Hawai’i, 1852–92. Law and History Review, 34(4), 999–1026. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0738248016000353

21. Tanenhaus, D. S., & Nystrom, E. C. (2016a). “Let’s Change the Law”: Arkansas and the Puzzle of Juvenile Justice Reform in the 1990s. Law and History Review, 34(4), 957–997. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0738248016000341

22. Tanenhaus, D. S., & Nystrom, E. C. (2016b). The Future of Digital Legal History: No Magic, No Silver Bullets. American Journal of Legal History, 56(1), 150–167. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajlh/njv017

23. Tarasov, N. N. (2001). Methodological issues of juridical science: monograph. Yekaterinburg: The Liberal Arts University Publishers. (In Russ.).

24. Valiev, R. G. (2016). On some theoretical and practical aspects of legal technique and technology. Uchenye zapiski Kazanskogo filiala Rossiiskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta pravosudiya, 12, 3–12. (In Russ.).

25. Vlasenko, N. A., Abramova, A. I., Arzamasov, Yu. G., Ivanyuk, O. A., & Kalmykova, A. V. (2013). Rule-making juridical technique: monograph. Moscow: The Institute of Legislation and Comparative Law under the Government of the Russian Federation. (In Russ.).

26. Volkaert, F. (2021). OK Computer? The digital turn in legal history: a methodological retrospective. Tijdschrift voor Rechtsgeschiedenis / Revue d’histoire du droit / The Legal History Review, 89(1–2), 1–46. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718190-12340011

27. Ward, R., & Williams, L. (2016). Initial views from the Digital Panopticon: Reconstructing Penal Outcomes in the 1790s. Law and History Review, 34(4), 893–928. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0738248016000365

28. Yudin, E. G. (1978). Systemic approach and the principle of activity. Methodological issues of modern science. Moscow: Nauka. (In Russ.).

About the Author

S. V. LonskayaRussian Federation

Svetlana V. Lonskaya – Dr. Sci. (Law), Associate Professor, Professor of the educational-research cluster “Institute of Management and Territorial Development"

6 Frunze Str., 236006 Kaliningrad

WoS Researcher ID: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/author/record/V-9227-2017

Google Scholar ID: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=gGpufQ4AAAAJ

RSCI Author ID: https://elibrary.ru/author_profile.asp?id=370137

Competing Interests:

The author declare no conflict of interest.

- new directions for studying the past of law and state using digital information and communication technologies and tools;

- digital humanities as a new interdisciplinary area and the heuristic potential of digitalization in legal historical sciences;

- combination of traditional and new methods of studying the history of law and state: methodology issues;

- research program of historical-legal source study and the opportunities for expanding ideas and knowledge of historical-legal facts, phenomena, and processes.

Review

For citations:

Lonskaya S.V. Digital History of Law: Principles of Methodology. Journal of Digital Technologies and Law. 2024;2(1):14–33. https://doi.org/10.21202/jdtl.2024.2. EDN: cfnahc